10 Year ADSC – End of the World?

I don’t hold back when people ask me the best way to become a military pilot. The Ultimate Military Pilot Career Path is to get hired directly by a Guard or Reserve unit and let them send you to UPT. Ideally, you should enlist with one of those units as soon as you’re old enough and serve part-time while you complete college. This eventually allows you to retire a full four years earlier than any other military aviator.

While I continue to assert this is far better than becoming an Active Duty pilot through the USAF Academy, ROTC, or OTS, I worry that I’ve done people a disservice by making the Active Duty pilot career path seem too unattractive.

Today we’re going to compare the more common Active Duty career path with the Ultimate one that I’ve recommended so heavily. We’ll see that the Active Duty option is still a good deal, that the overall difference isn’t so great, and we’ll see why you’re better off pursuing either than trying to fulfill a non-pilot commissioning commitment before trying to pursue the Ultimate career path. We’ll also see some advantages of Active Duty and some options for cutting your time there short.

Table of Contents

- Feeling Gun Shy

- Case in Point

- Comparison

- Start With Why

- Active Duty Benefits

- Back to the Question at Hand

Feeling Gun Shy

The big gotcha of the Active Duty pilot career path is that on the day you earn your wings, you also get hit with a 10-year Active Duty Service Commitment (ADSC). For the next decade of your life, you will deploy a lot and have little or no control over your assignment locations. It’s a lot to ask.

The US Army recently changed its aviation Active Duty Service Obligation from 8 to 10 years and created an absolute uproar. (Yes, they say ADSO instead of ADSC because the Army and the Air Force refuse to do anything the same since they divorced back in ‘47.) I remember similar drama during my Fourth Class (freshman) year at the USAF Academy as we were forced to sign a paper accepting a similar ADSC increase in case of getting an Air Force pilot slot.

I’d always wanted to be a pilot and didn’t know anything else, so I said the Doolie equivalent of “Shut up and take my money!” (There was a lot more “Sir” and “Ma’am” involved.) However, many of my buddies weren’t sure yet if they were willing to commit to a decade of service in exchange for a pilot slot.

Now that I’m older and wiser, one of my many side-hustles is working as an Admission Liaison Officer for the USAF Academy. In recent discussions with some USAFA cadets, I’ve encountered several who actually turned down pilot slots because of that 10-year ADSC. This mindset is far from universal, but it’s prevalent enough that the Academy actually had pilot slots go unfilled a few years ago! This used to be unheard of. And yet, there’s a certain logic to questioning that 10-year commitment.

Case in Point

One Academy cadet I spoke with (let’s call him Stan) has always wanted to be a military pilot. However, he missed out on that Ultimate Military Pilot Career Path and is concerned about a 10-year UPT ADSC. He was thinking about turning down an Active Duty UPT slot and fulfilling the alternative 5-year USAFA non-pilot ADSC as an engineer or something, then pursuing a UPT slot with a Guard or Reserve unit.

Stan figured that even spending 5 years in a non-flying job, this track would make him a military pilot well below the USAF’s current age limit (33 years old), and would actually get him to the airlines sooner than his Active Duty pilot peers.

As a good mentor, I knew to ask lots of questions and take the time to dig down to the primary factors motivating this line of thinking. I ended up discovering that Stan was most worried about frequent moves and long deployments stressing his family during an Active Duty flying career.

At first, his idea sounded reasonable to me. It does have the potential to get him to the airlines more quickly, and he’d do all of his military flying in the Guard or Reserve (with Quality of Life far superior to Active Duty, in most cases). However, after spending a few more minutes thinking about how these career paths might compare, I decided Stan’s idea might not be as advantageous after all. Let’s compare these options to see why.

Comparison

In order to figure out the pros and cons of these different options, we first need to compare the timelines side by side. We’ll look at three cases:

- Ultimate Military Pilot Career Path (Attend UPT as a Guard or Reserve pilot)

- A “regular” Active Duty pilot career path. (We’ll assume a move to the Guard or Reserve after completing your initial 10-year UPT ADSC. I’ve also called this the Ideal Military Pilot Career Path.)

- Stan’s idea (Do 5 years as an engineer, then fly for the Guard or Reserve)

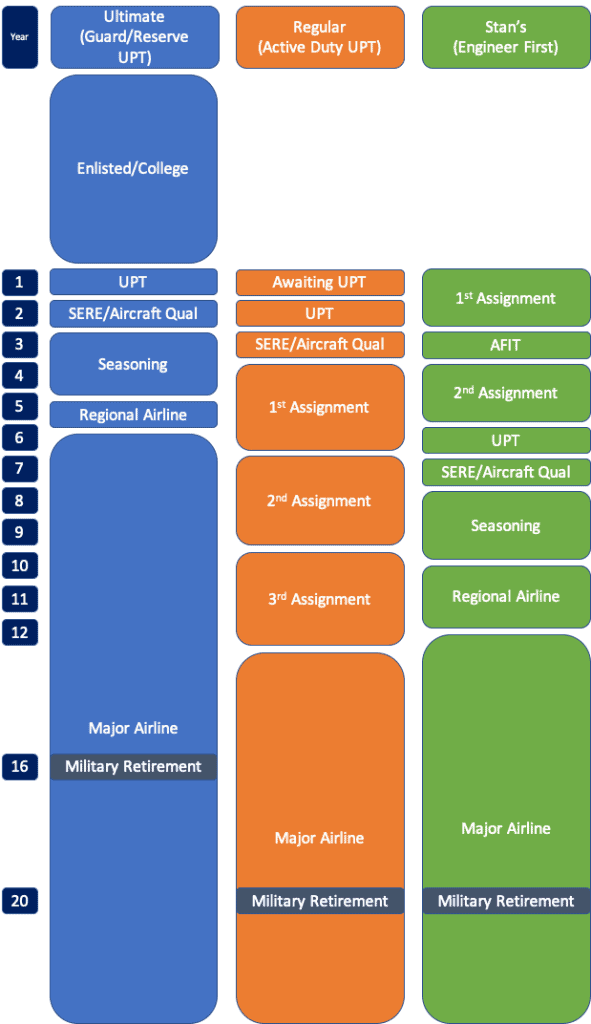

Although each of these career paths has potential for almost infinite variation, this diagram represents likely versions of each:

Looking at these side by side, it’s clear why #1 is the Ultimate option. You get to the airlines sooner, and you spend more years at a major airline. However, on the surface, we see that Stan’s plan is likely to get a pilot to the airlines a couple of years before his peers. In the current COVID crisis, those years may soon make the difference between having a great job and getting kicked to the curb as a furlough. It turns out that even one year is a big difference. However, we have to look at more than just the number of years involved.

Stan was worried about his Active Duty career path (Option #2) because it would ensure several years of moves and deployments. In a worst-case scenario, he’s looking at:

- Moving to a random Air Force Base for less than 1 year while Awaiting Pilot Training (APT)

- Moving to his UPT base for 1 year

- TDYs (multi-week business trips) for SERE and water survival

- Possibly a TDY for Introduction to Fighter Fundamentals (IFF)

- Moving to a base for 6-10 months for initial aircraft qualification

- 2-4 more moves for assignments during his Active Duty career.

Wow, that’s a lot of moving and time away from home! Then it gets worse: Over the past 19 years, an Active Duty pilot has also been likely to spend half or more of those operational assignments deployed. Deployments are great flying, but terrible on a family.

While Stan’s Option #3 seems to bypass a lot of this, let’s look at what he’d have to do:

- If Stan becomes an engineer in the Air Force, he’d probably have to attend some sort of training right after graduating from college. This could be a few weeks TDY, or a multi-month move.

- Next, he’d go to his first assignment. He’d probably get 2-3 years at that assignment, but if he did a good job the Air Force would offer him the chance to get a Master’s Degree through the Air Force Institute of Technology (AFIT) at Wright Patterson AFB. This is usually a 1-year assignment, though it might be two.

- After AFIT, Stan would owe a payback for school and might have to serve longer than his 5-year non-pilot ADSC. If he didn’t go to AFIT, he’d have to move for a second assignment anyway.

- Stan is likely to do plenty of TDYs as an engineer and isn’t impervious to the threat of deployment. Unlike pilot deployments that can be as short as a couple of months, engineer deployments are usually 6-12 months.

- During this time, Stan would at least need to obtain his Private Pilot Certificate. Ideally, he’d also earn his Instrument Rating, and build as much experience as possible. (Read this BogiDope article for a discussion of these options and their advantages.) This is both expensive and time-consuming…tough to fit in around a 9-5 as an engineer, especially if he has a family.

- As Stan would be finishing up his 5-year ADSC, he’d need to be shopping for Guard and Reserve UPT board announcements on BogiDope’s job postings page. Once he identified some units in which he’s interested in, he’d need to start rushing each of them. These trips have to be funded at his own expense and would require him to use leave that won’t be available for family trips.

This plan assumes that Stan can get hired by a Guard or Reserve unit at this point. While it’s not impossible, and BogiDope can absolutely help you get there, this is far from guaranteed. What if Stan’s 5-year ADSC runs out as the next SARS/Swine Flu/COVID-type pandemic puts hiring on hold? Even just a year or two of delay erases any possible advantages of this career path.

Let’s assume though that Stan can get hired by a unit, and is scheduled to start UPT as soon as his regular ADSC is up. He’d still have to go through steps 2-5 from the Active Duty pilot career path above! That’s at least 2 moves and several TDYs in the space of about 2 years. Having been out of college for at least 5 years at the start of UPT, it’s more likely that Stan will have a spouse and kids…making the very busy year at UPT even more challenging.

Once Stan finally gets qualified in his aircraft, he’d get seasoning orders with his Guard or Reserve unit. These could range from 6 months to two years, depending on the type of aircraft he’s flying. This means a steady paycheck and decent home life, except that as the newest pilot in the unit Stan is at the top of the list to deploy if the squadron gets sent downrange. His deployment vulnerability continues for even a couple of years after his seasoning orders are over.

As long as he’s getting a lot of flight time, Stan should have enough hours for a Restricted ATP rating and a shot at a regional airline job a couple of years before his Active Duty pilot peers. However, has he really had a better home life than them?

Stan’s family has still moved several times…both as an engineer and as a pilot. He’s likely deployed at least 3 times, if not more, and has also spent many weeks TDY. On this career path, Stan is most likely to leave young kids at home with his spouse while he deploys. If he’d gone to UPT right after college, it’s more likely that he’d get a lot of his deploying done before his kids were that old, or even before they were all born. All in all, this track has the potential for less family stability than his Active Duty pilot counterparts.

Suddenly, Active Duty isn’t looking that bad, right?

Start With Why

When discussing any big-picture career options, I always make sure to follow Simon Sinek’s advice and Start With Why.

For anyone facing a 10-year military pilot ADSC/O, this means asking yourself: “What is it about military flying that made you want to do it in the first place?”

For most, Top Gun played at least a little bit of a role. There’s no debating that the military has a near monopoly on the most exciting aviation available to humankind. The pay and benefits aren’t bad, and patriotism also factors in for most of us.

My talk with Stan covered all of these, so my next question was, “How long were you planning on being involved in military aviation then? Were you planning on doing it for less than 10 years?”

His answer was, “Of course not. I want to do it for as long as I can. I like the idea of the Ultimate career path because it still allows you to earn a 20-year military retirement.”

I’ll tell you what I told him:

If you want military aviation to be a part of your life for more than 10 years, possibly even 20+ years, you should pursue any path that will get you there!

Yes, most of us eventually plan to move on to the airlines. Yes, life there is fantastic, and it’s important to get there as quickly as you can because Seniority is Everything. However, I don’t think it’s worth passing up a nearly guaranteed Active Duty UPT slot in hopes of possibly getting a Guard or Reserve slot 5 years from now.

It’s important to note that Stan’s theoretical plan might have allowed him to obtain the 750 hours needed for an R-ATP about 7 years after graduating from college, but that’s not competitive for getting hired at a major airline. Stan’s Active Duty pilot peers would have spent 8-11 years since graduating from college flying for the military full time. They might be stuck on Active Duty slightly longer than Stan, but he’d have to spend at least a couple of years at a regional airline to even start competing for major airline jobs. Like it or not, you need to accrue that experience one way or another. That evens the odds even more.

Active Duty Benefits

Although I like to poke my Active Duty friends in the chest by asking, “What do you love about military aviation that you can’t also get in the Guard or Reserves?” I’ll admit that there are some benefits to Active Duty military service.

First, as we just mentioned, you only have to worry about one job – flying one aircraft for Uncle Sam. As a Guard or Reserve pilot, you may need to find a full-time flying job in addition to your military flying (full-time Guard/Reserve pilot jobs are available, but you should join with the expectation of needing civilian employment in addition to your military flying). This means keeping up with at least two airplanes and dealing with two potentially very demanding bosses.

There are also a lot of great flying opportunities that you can only do on Active Duty. If you want to fly the U-2, you must start on Active Duty. The same goes for great deals like going to Test Pilot School, flying the E-11A BACN, and much more. Serving on Active Duty is also the only way to get an overseas flying assignment. My family got to live in England for three years and it was fantastic!

If you’re worried about frequent moves disrupting your family life, picking a community with few basing locations is a viable option for Active Duty. Aircraft like the E-3 don’t have many bases. The U-2 and B-2 are both single-location aircraft, and they go through so much trouble getting their pilots that you’d have to try to leave.

Although it’s easy to feel stuck on Active Duty, there are also options for getting out early. The Palace Chase program exists specifically for Active Duty pilots willing to make an early commitment to continue their service in the Guard or Reserve. Although it’s less common to get more than 6-12 months of your ADSC forgiven under this program, that still gets you off Active Duty sooner than expected. The earlier you can Palace Chase, the less difference there is between a regular Active Duty pilot and someone following Stan’s plan.

Back to the Question at Hand

Having looked at these options, let’s go back to our original thought:

If you missed your shot at the Ultimate Military Pilot Career Path are you screwed? Is a 10-year Active Duty ADSC so terrible that it’s worth passing up?

I say, absolutely not!

Although 10 years of Active Duty feels like a long time, it’s not that much longer than the alternatives. Serving on Active Duty has plenty of advantages, and even offers some highly-desirable opportunities that you can’t get anywhere else.

Yes, the Ultimate Military Pilot Career Path is the best – it gets you to all of your goals the fastest. However, if you missed that boat you’re far better off taking an Active Duty UPT slot than trying Stan’s way and doing 5 years as in a non-flying job.

All of military aviation is what you make of it. If you love the flying you’re doing, and you have a squadron of good people, any assignment can be a great experience, no matter how busy you are.

Whatever path you end up taking, please consider taking a UPT slot when offered. Our nation needs brave men and women willing to use Air Power to murder our enemies and break their shit. That means, we need you!

Image Credits:

F-35s in feature image: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/3982524/f-35-sky.

F-22 crew chief: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/4798866/f-22-europe.

The B-2 about to get fuel: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/5765915/b-2-and-boom.

Deployed Civil Engineers https://www.dvidshub.net/image/491088/deployed-civil-engineers.

C-17 formation from the ramp: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/6100141/c-17-air-drop.