Curing The Pilot Disease Worse Than COVID-19 – Part 2

Welcome back! It’s time to conclude our examination of a disease that I call Wingman or Copilot Syndrome. We started this series by exploring some ways to identify this syndrome. Last week, we looked at some ways to cure it.

Now, it’s time to look at ways that some ineffective ways that people try to compensate for their shortcomings. These ineffective therapies may be done with the best of intentions. A pilot may fully realize that he or she has contracted Wingman Syndrome. However, instead of addressing the root of the problem, they try to compensate with something else.

Within our disease analogy, this might be like treating lung cancer with a lobotomy. It’s a big, grand gesture that requires total commitment. However, it’s just not going to get the job done.

Table of Contents

Ineffective Therapies

Quibbling, Deflecting, and Defending

These three strategies are variations on a common theme. They tend to be the #1 go-to for pilots ailing from Wingman Syndrome because they’re quick and require the least amount of intelligent thought to employ.

Quibbling is trying to excuse your own poor performance by pointing out or even starting an argument about something trivial, and frequently unrelated. Deflecting is similar to quibbling, but focuses on pointing out or blaming another person for a different shortcoming. Defending, in this context, essentially means arguing that having Copilot Syndrome is okay.

An example of this might be a pilot so preoccupied with other thoughts that he or she tends to miss frequency changes (from ATC or from the Flight Lead.)

If the FL calls this pilot out in a debrief, the proper response would be, “You’re right sir/ma’am. I sucked at that because I didn’t have my head in the game. I’ll do better.”

If pressed, the pilot should even be able to explain how he or she intends to make those improvements. Some examples might include: listening to Live ATC for the area to get used to the cadence of frequency changes, doing a better job of knowing the mission plan and thinking ahead for what’s coming next, and taking care of everything else in life more effectively so that it doesn’t have to occupy brain bytes while flying.

Some improper responses to this debrief might include

- “Yah, but you briefed we’d get sent to 134.75 on departure and we actually got sent to 128.9. It’s not my fault your briefing was wrong.”

- Or worse: “Yah, but did you realize that in your approach briefing you incorrectly stated that this runway has a VASI when it actually has a PAPI? I don’t think your head was in the game either.”

- “Yah, but my jet was acting up today. Every time I turned left, the digits on the fuel flow display changed to dashes. Aviate comes before communicate.” (If it was an actual issue, you should have mentioned it in the air.)

- “So what? I was in position and on course.”

I’ve noticed this strategy a lot from commanders and bosses who contract Wingman Syndrome when they let non-flying tasks get in the way of flying so much that their skills deteriorate. They’ll say, “Keep an eye on me. I’ve been busy with [Insert Project Name Here] and haven’t been getting to fly as much as I’d like.”

What this really means is, “At this point in my career I’ve prioritized other things over flying and willingly allowed my skills and knowledge to atrophy. Rather than put in extra effort to prepare for this event and focus hard on the task at hand, I’m just going to accept substandard performance and rely on you to keep me from doing anything dumb enough to lose my wings.”

Granted, if you’ve willingly allowed your Copilot Syndrome to get this bad, you owe it to the person you’re flying with to admit when you aren’t ready. However, the better way to address this situation would be: “I’ve been slacking as a pilot lately. I prepped for this event by spending some quality time in the simulator a couple days ago, really focusing on mission planning, and I even did a little chair flying last night. I’m going to use every moment of this flight to regain proficiency. However, don’t let the Halo Effect prevent you from correcting me if I need it.”

There are times when a pilot may knowingly and willingly expose him or herself to Wingman Syndrome. We’ll talk about how to approach that later. However, that doesn’t mean this Syndrome itself is ever a good thing. There is never an excuse to defend it, and trying to quibble or deflect your way out of facing it is just a pitiful combination of willful ignorance and moral cowardice.

Aggressive (vs Assertive)

I’ve mentioned many times that “Drive it like you stole it!” is fundamental to my philosophy as a pilot. As pilots, we must know your capabilities, authorizations, and limitations. We must not hesitate to execute our mission or flight plan within those bounds. Sometimes, we have to be willing to choose a course and stick with a course of action, even though circumstances don’t clearly fit within our established procedures.

I call this being assertive, and it’s a critical skill for pilots to develop. As a T-6 IP at USAF UPT, I worked hard to instill it in my students. My life got measurably better when Stan finally caught on and quit asking “Mother, May I?” in between every maneuver or radio call.

Like most good things, it’s easy to take the idea of being assertive too far. I find that some victims of Wingman Syndrome try to cover their shortcomings with what they think is assertiveness. However, since they’re trying to excuse the inexcusable, assertiveness doesn’t work for them. Instead, they overshoot badly and end up employing mindless aggression instead.

You can’t miss this when you see it. When a pilot receives a critique during a debrief, he or she gets visibly angry. He or she may immediately start quibbling or defending, but this gets accompanied with a raised voice, inelegantly-employed profanity, and even aggressive body language.

I’ve seen this with mission planning or regular ground duties too. A supervisor might ask Joe Pilot why Task X isn’t done yet. Joe immediately starts yelling about how it’s not his fault, listing all the circumstances that caused his poor performance. Joe might even step up to his supervisor and stick a finger in his chest to help make the point.

You’ll also notice unnecessary aggression in this person’s flying. When assigned slam-dunk vectors on approach, Joe Pilot will never, ever consider setting things up again. He always presses on, no matter how fast and unstable he is…as he trucks down final without his gear down.

In formation, Joe always initiates maneuvers with the maximum g-load allowed, and frequently overshoots. Being his wingman is a nightmare. Nobody flies like Joe because it’s tough to follow and it’s a waste of energy. Joe’s out to prove what a great pilot he is though. If anyone complains about him being tough to follow, he belittles his wingman for being an inferior pilot who “can’t hang.”

Joe doesn’t fly like this because he’s that good. He flies like this because he sucks in some other area of his job. Instead of fixing the problem, he relies on this raw aggression to make up the difference.

Pilots like Joe break aircraft and get people into trouble. At best, most commanders sideline these pilots and “promote” them to new opportunities as soon as possible. However, what Joe really needs is someone to sit him down, talk about what he’s actually weak at, and get him to focus on that instead of trying to overcompensate with aggression.

This isn’t to say that there’s never a time for aggression in aviation. A fighter pilot in an air-to-air engagement should be aggressive. A C-145 pilot landing on a dirt road in front of a Forward Operating Base in a gusty crosswind has to be aggressive. However, this is done in a very practiced and standardized manner. This type of aggression is based on a foundation of knowledge, practice, and attained proficiency. I use the term “assertive” to differentiate this type of conscious, prepared aggression from the mindless rage that some pilots try using to Hulk-smash their way through life.

Assertive is great. You should absolutely cultivate it. If you find yourself active aggressively, step back and ask why. Hopefully, you’ll see what you’re trying to compensate for and fix that area instead of causing everyone around you problems.

Irrelevant Deep Dives

Another way I see many pilots trying to make up for weaknesses is by diving deep on something that won’t address the weakness itself.

This could be a fighter wingman who is just slow with HOTAS swichology. What he needs is to practice the basics. Instead, you might see the wingman in question start doing a ton of research about the Su-57.

He or she digs through SIPRNET to find out all kinds of obscure data about the jet’s capabilities, radar cross section, tactics, etc. He might even put together a slideshow on the jet and ask the weapons officer for permission to brief the entire squadron about it.

Under other circumstances, there’s nothing wrong with a wingman going above and beyond to prepare a threat brief, even if it’s highly unlikely the squadron will encounter that aircraft. However, this particular wingman is the one who can’t even manage to get a radar lock on his assigned target because he hasn’t built the switchology habit patterns he needs.

What this wingman really needs is to spend a lot of time in the sim practicing simple tasks over and over again. It’d probably only take a few hours to get proficient enough to do his job well. At that point, he could move on to his fancy threat brief. However, by using an ineffective Wingman Syndrome therapy, he’s preventing himself from fixing his problems and highlighting himself as a fool at the same time.

I once flew a series of combat missions in Afghanistan with a copilot who was close to Aircraft Commander upgrade. We were at Mazar-e-Sharif, an airfield with a single runway positioned such that we frequently had a crosswind. Not only could my copilot not accomplish a passable crosswind landing, he seemed oblivious to the conditions altogether.

At the time, the Air Force was putting way too much emphasis on pilots having a Master’s Degree and completing Professional Military Education. (Well actually, that hasn’t changed.) This copilot looked like a star on paper because he was deep into his Master’s program and had completed SOS in correspondence years before he’d even be considered for in-residence attendance.

He spent a lot of time working on those things, yet he couldn’t manage a simple crosswind. Yes, he was working hard, but the effort wasn’t addressing the most pressing concern.

I’ve also seen pilots use mission planning or special projects as ways to make up for weak flying. Last week, I suggested that a pilot who is specifically weak in mission planning could work to plan a special training event. This is a great thing to do if that’s your weak area. However, what if you’re the only pilot in the squadron who can’t seem to hang on the refueling boom for longer than a few seconds at night or in IMC?

You could spend weeks trying to plan special training missions at cool locations, but if you aren’t capable of accomplishing such a fundamental task as taking on fuel, mission planning is the last way you should be spending your time.

This pilot should instead be studying, practicing in the simulator (assuming it offers decent AR training, unlike the B-1 sim), and begging scheduling to put him on training flights scheduled for refueling.

I suspect that some parts of the Navy may be better than the Air Force on this. For a while the USAF CSO pipeline was so backed up that the U-28 couldn’t get enough bodies to go to war. (40% of the community was deployed at all times.) The Navy ended up sending some NFOs and pilots to man our CSO sensor operator station.

One of these pilots, we’ll call him Sally, had flown both the F-14 and F-18. He was a good dude overall, and our variety of experiences made for some fascinating discussions on long combat missions. One day he told me about how both of his aircraft are capable of some crazy, advanced maneuvers. However, if done incorrectly, these maneuvers are extremely dangerous. As such, there was a rule in the fleet that a pilot was not allowed to try these maneuvers until he or she had sufficient experience. (I think it was on the order of several hundred hours.)

He didn’t make a big deal about it, and I gather that it wasn’t some special certification that a USAF pilot might chase as an extra bullet for a performance report. It was just a fact of life that Navy pilots accept for their own good.

I believe that’s the right line of thinking. This rule, written or not, made sure that pilots attained basic proficiency before attempting anything advanced. Well done Navy. (Now get back to floating on your boats.)

Patronage

Another ineffective Copilot Syndrome therapy I’ve observed is when a pilot relies on a Patron to bestow things upon him, instead of earning it through hard work and competence.

You’ve probably seen this too. It’s common knowledge that a particular individual is weak in some area. All of a sudden, this pilot appears on the upgrade list for a qualification that others definitely deserve more and you’re not sure why. Sometimes, the upgrade happens because a high-ranking officer made a very compelling suggestion to a squadron commander or training officer.

Don’t be that pilot.

You’ll know you are that pilot if you yourself frequently mention a particular senior officer in everyday conversations.

“Oh yeah, I heard something about that. Colonel Desktop mentioned it to me the other day and said….”

“Well, that’s not actually the problem. You see, Colonel Desktop tried to do this, but got denied….”

There’s nothing wrong with having a mentor. In fact, I’m looking forward to discussing Mentoring in an upcoming BogiDope article. However, we’ll learn that the purpose of having a mentor is not to gain unearned things.

As a Company Grade Officer (CGO), you should have good working relationships with the O-4s and O-5s in your squadron. They could be your Shop Chiefs, ADOs, Department Heads, and even Flight Commanders. However, there’s no reason for a CGO to have such a close relationship with a Squadron Commander or any O-6+ that he or she has reason to regularly name-drop like this.

The one exception here is that (in the Air Force) most Squadron, Group, and even Wing commanders select senior Captains as their Executive Officers. This job does make you privy to all kinds of information and opinion directly from a senior officer. It’s okay to convey information to your buddies, but these jobs are to Wingman Syndrome like Italy was to early Coronavirus. You’ll have to work harder than anyone else not to catch it!

If you are an Executive Officer, it’s worth taking a moment to transition your mindset before you walk back into your old flying squadron. Remember that despite the important, shiny things you work on all at the Big Boss’ office, when you come back to fly your proficiency is all that matters. Focus on the task at hand, and do everything in your power to maintain the skills that your desk job will try to take from you.

Before we conclude our discussion on Patronage, I’ll say that just because you aren’t supposed to be buddies with senior officers, it may still be appropriate to discuss important matters with them. Every pilot needs non-flying career progression, and you won’t get what you want unless you discuss it with your chain of command. If you have questions that go beyond the scope of your Squadron Commander’s authority, it’s okay to reach higher. However, make sure your boss knows what you’re doing. Your best bet is always to have your boss set up that meeting for you. Most Squadron Commanders are more than happy to do this when it’s appropriate.

We’ll talk more about how to balance necessary career development against relying on brown-nosing and patronage to get picked for upgrades you aren’t ready for when we talk about mentoring.

Balance

After I posted the Symptoms portion of this series, a friend made a good point. Although he admitted that my observations were right on, there’s also a need for balance in life. I absolutely agree. I believe that all of the military’s pilot retention problems stem from a failure of balance.

It’s very easy to say, “I don’t ever want to contract Wingman Syndrome! I’m going to spend every waking moment implementing every strategy Emet mentioned to keep myself inoculated.”

Unfortunately, the person who does this will stay or end up single and burned-out. It’s the equivalent of our government saying, “We must fight COVID-19 by quarantining everyone for the next 2 years! Nobody out of the house except grocery stores for any reason!” We might not die of Coronavirus, but we’d probably all go crazy. We’d also emerge to an economy so wrecked that there’d practically be nothing to leave the house for. At some point, we have to balance both sides of that equation.

It is absolutely critical to balance all of our personal needs in life: family, intellectual, social, health and fitness, spiritual, professional, etc. Flying, in a military unit or at a civilian operator can meet some of these needs, but it can’t do all of them. If you focus too much time and attention on a few at the expense of the others, your life will fall out of balance and you will end up an overall failure.

I mentioned that I’m proud of Francis, my A220 Captain who had spent the last 12 years as an A330 FO, for choosing to complete his initial Part 121 airline Captain upgrade at 63 years old. However, I’m also happy that he’d enjoyed the last 12 years so much. He’d willingly accepted a mild case of Copilot Syndrome in order to let him maintain balance in other parts of his life.

He’d spent lots of time with his family and friends. He’d enjoyed his life after a long career as a military officer that concluded as an O-6 Vice Wing Commander. I imagine that most USAF O-6s could use 12 years to relax before taking on a Captain upgrade.

I look forward to spending at least a few years following Francis’ footsteps. I’ll bid into a category where I’m very senior and/or rarely used…probably A350 FO. I’ll bid reserve and probably only get called a couple of times a year. I’ll end up going to the simulator in Atlanta for my 3 landings every 90 days because I’ll fly so rarely in the actual jet.

I’ll use that time to build an airplane, teach my kids to fly it, follow my kids around on a traveling sports team or musical group, sip margaritas on as many beaches as possible with my wife, and/or start a business.

That will be every bit as good a life as I lead now, working a whopping 10 days a month while bringing in the big bucks as an A220 Captain. My focus will be elsewhere, but it’ll allow me to shift the balance of my priorities for a while.

I’ll have to be a little careful when I go fly. I’ll need to do some intentional studying and chair flying to make sure I remember how to start the engines and raise the gear. Then, when I’m ready, I’ll abandon that easy life and go back to working for a living as an A321neo Captain or whatever else sounds fun at the time.

Overall, I believe that Wingman Syndrome is something to avoid. However, there’s no point in fighting to eradicate it at the expense of everything else in life. Fighting Copilot Syndrome is like aircraft design, with give and take in every part. You probably can’t fill all the seats, the entire cargo compartment, and take full fuel. Do your best to optimize each flight based on your needs at that moment. If you have to leave a little behind on this flight, pick it up on your next time through. When you identify a weakness, use an effective strategy to address it. Then move on with life and take care of the next priority.

I wish you all luck in avoiding both the ‘Rona and Wingman/Copilot Syndrome. Fly safe out there.

< Back to Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

Image Credits:

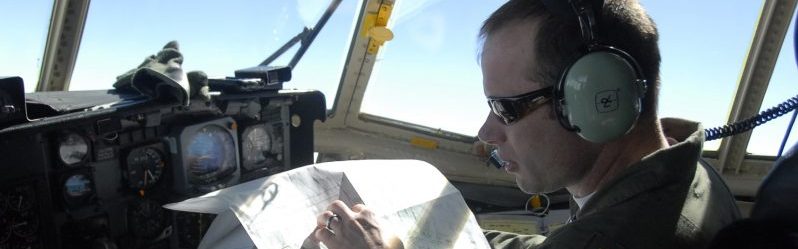

This post’s feature image is from: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/1096379/c130-aircrew-positions-copilot.

Rusty CH-47 pilot: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/6136762/flying-freight-trains.

Я нашел картинку Су-57 здесь: https://en.topwar.ru/170908-bumerangom-vsled-su-57.html. Если вам обидно, что ее использовал, пожалуйста пиши к: daladnotebye@gmail.com.

Afola’s picture is from: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/4223400/military-working-dogs-demonstrate-controlled-aggression-tactics.

The O-6 mentoring photo is from: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/4001858/chaplain-chaplain.

A-10 pilots debriefing: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/4428029/10-operations-kandahar-airfield.

Family at Fini Flight: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/5630517/pilot-family-celebrate-fini-flight.