Functional Tracks in Army Aviation: Part II

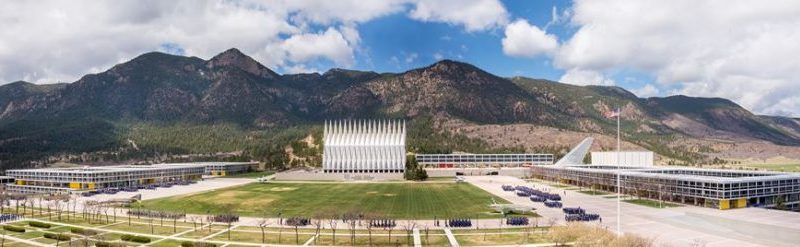

Photo Credit to Defense Visual Information Distribution Service

Welcome back.

So just as the information about Functional Tracks needed to be split into two weeks, realistically, the introduction did as well. This is because I wanted to give a special emphasis to explaining their purpose and the importance of selecting, pursuing and ultimately thriving in a selected functional track up front. This week, I want to just clean up with some administrative “good-to-know”s and “good-to-do”s to assist you in learning more and, ultimately, selecting a Track when the time comes.

As I mentioned in last week’s introduction, ultimately, networking is king. It allows you to get real, up-to-date info. on the job and, likely, to see it being done. If you’re a qualified pilot in the Army, untracked and considering your options but haven’t started spending serious time with tracked-pilots to get insight into the scope of their jobs, you’re doing yourself a disservice (I sincerely hope there are none of those reading this). Start talking with the tracked pilots. If you’re a prospective Army Aviator who’s currently enlisted, find a way to get in contact with some tracked aviators and pick their brains. There are at least a few pilots at every Army installation where Active Duty types could be stationed and there are pilots in the National Guard in every state of this Union. If you’re not yet in the Army, find a local Army National Guard recruiting office and ask the recruiters to get you some contact information for pilots. We'll even have a map listing all of the units in the Army Guard and Reserves up on the site in the next few weeks to help you out. So begin reaching out to units. That networking will also go a long way toward getting your foot in the door for a unit, should the Guard be your desired service component

Now to soothe those who stress about decisions… It’s worth noting that becoming “dual-tracked” is a very real probability, particularly if one displays passion and a good work ethic (just as becoming qualified in more than one aircraft over the course of a career is a very real possibility). When a pilot has tracked AMSO, for instance, and has displayed a capacity to absolutely crush that job, they will likely also be given the opportunity to become an IP or an MTP. Upon returning to their unit, they will still be assigned a slot for ONE of these two jobs, which is where their primary focus should ultimately be placed. But dual-tracked WOs are a massive boon to their units, as they are the experts in their assigned job but are also able to step in and assist in ensuring the other functional areas in the unit, and their associated programs, are strong.

So regardless of what Track you ultimately decide to pursue, be the type of person/pilot that will be selected to become dual-tracked and, in all likelihood, you will. Go ahead and add that fact to your career-calculus. If you’re a decision-stressor, let it bring you some sweet relief. The fact of the matter is, if you prove yourself to be a dedicated worker and a team player, Army Aviation really can be your oyster. It’s up to you to figure out how best to crack it.

If this is the first article you’re reading, do yourself a favor and at least read last week's article first.

Table of Contents

Maintenance Test Pilot (MTP)

These are the “Aircraft Whisperers.” The ones who gently pat a bird on its nose and politely ask it to work, then take it for a flight to make sure it keeps its promise. The ones you can give a tail number to and they’ll say, “Oh yeah, that aircraft has a slight shudder at 70 knots but don’t worry, she’s smooth as butter after that. Oh, and she likes the smell of sunflowers.” I can’t stress enough how vital each individual Functional Track is to the successful conduct of Army Aviation operations, and I wouldn’t dare say one is more important than the others because that would simply be untrue…but broken aircraft can’t fly. This is a statement both of how crucial it is to have quality maintainers - and for officers, both O- and W-grades, to take good care of those maintainers - but also how crucial it is to have quality MTPs. A batch of good MTPs can make the lives of their Platoon Leaders (PLs) and their Commander (CDR) infinitely less stressful, as they will be the hub cap on the wheel of the unit maintenance program. They’ll ensure that there will always be aircraft available for training and operations to be conducted and that aircraft downtime is minimized/optimized. Though this, by no means, should be an excuse for PLs and CDRs to just turn a blind eye and hope for the best (the maintenance program belongs to them), it means they can expend less energy and time checking in on the little things knowing their MTPs have it covered.

As with the IP Track, the formal training to become a MTP is dependent on the airframe for which a pilot is training, though they’re all roughly eight weeks at Fort Rucker (+- a week). Once a Warrant has completed the training, they will return to a line company and begin the real process of intimately getting to know the Company’s maintenance program (in the Guard, a Warrant who’s aspiring to become a MTP will likely already know the program intimately), the Company’s aircraft, and putting themselves in a senior-MTP’s pocket. Like most things in life, it’s very much a “train to gain the title, work to gain the know-how” scenario. I would also encourage those opting for the RLO-route to start building a relationship with your Company’s MTPs the MOMENT you get to your first unit or doing it while a cadet if you’re in the ROTC and drilling with a unit. As a PL, you WILL be ultimately supervising the maintenance program, ensuring the maintenance flow won’t lead to log-jams where no aircraft are available, etc. The MTPs will best show you what right looks like and teach you how to do that job, as they’ll be the ones with their hands actively in it all of the time.

Beyond monitoring and assisting with the flow of the maintenance program, MTPs conduct Maintenance Test Flights (MTF). Following aircraft maintenance, a MTF is required to ensure that the given maintenance fixed what it was supposed to fix and that the aircraft is fit for flight/mission capable. The prospect of conducting MTFs is an uncomfortable one for many, given that the individuals conducting it are taking an aircraft that hasn’t been certified “completely flight worthy” and certifying it as such by playing with its limits. Obviously, the process has a massive amount of steps built in to prevent an aircraft taking off that really shouldn’t, but still…some balk at the idea. And that simple fact is what drives many away from wanting to be MTPs. But MTFs are a quintessential part of the job and they’re also where MTPs can build up a TON of hours in the aircraft, as there are always aircraft in need of MTFs so they can get back out of the hangar and into the air. And then, beyond MTFs, the MTPs are additionally conducting missions and training flights along with all of the other aviators in the unit. It adds up and it adds up fast.

The career progression of a MTP is also akin to that of an IP. After serving at the CO and BN-levels, a MTP can become a Maintenance Test Flight Evaluator (ME). Becoming a ME doesn’t require a formal school or training pipeline, rather, a MTP will undergo an evaluation (a lengthy and VERY in-depth evaluation) that will determine whether they are experienced and capable enough to conduct evaluation flights on other MTPs. Just as all pilots have their annual flight and knowledge evaluations, MTPs and IPs have additional evaluations and tasks annually to ensure they’re still fit for those jobs.

Oftentimes people who love working on cars, small motors, etc., thrive as MTPs. It’s a job that gets you out of an office, onto a hangar floor or flight line and occasionally oily, which makes some people absolutely eat it up. And some people sincerely love the thrill of conducting power-off autorotations, which (hopefully) won’t be conducted anywhere other than a MTF (or a no-crap dual-engine failure). If that sounds like you, talk to a MTP.