How to Become a Fighter Pilot

Have you seen Top Gun or any of the (objectively terrible) Iron Eagle movies more times than you’re willing to admit? Do you daydream of flying twice the speed of sound, pulling 9Gs, and dominating the airspace over any country on the planet, at will? Perhaps you’re motivated by the idea of protecting troops on the ground through close air support or just being a part of an elite aviation fraternity (for both guys and gals) full of rich history and tradition. If any of this sounds like you, serving your country as a fighter pilot may be the perfect career (and calling) you're looking for.

One of the questions we get most often here at BogiDope is: “How can I become a fighter pilot?” We’re not surprised at how often we hear this. In many ways, flying a fighter is the pinnacle of human aviation. It’s both incredibly demanding and incredibly rewarding. Our hope is that what follows will serve as a useful answer to this question.

Table of Contents

- Choose a Path

- Academic Preparation

- Physical Preparation

- Aeronautical Preparation

- Social/Cultural Preparation

- Execution - How to Get a Guard/Reserve Fighter Pilot Slot

- Execution - How to Get an Active Duty Fighter Pilot Slot

- Conclusion

Choose a Path

There are two main paths you can take to become a fighter pilot, Active Duty or Guard/Reserve. Both paths can lead to the same destination, but there are critical differences as to how to get there and quality of life along the way.

Active Duty

The first path is serving on Active Duty (i.e. Air Force, Navy, or Marine Corps). This is what most people think of when they picture someone serving in the military. Being an Active Duty pilot is a full-time job. You show up for work 5 days per week, whether you’re flying or not. This path offers fantastic pay and benefits and a government pension if you serve a full 20 years.

The Active Duty path essentially entails competing for the opportunity to attend pilot training while earning a commission through a service academy, ROTC, or OTS/OCS. Then you will commit to 10(ish) years of full-time military service before knowing what airplane you will fly. (You commit to 10 years after completing pilot training in the Air Force, only 8 years in the Navy and Marine Corps.) This leaves you beholden to the whims of the Air Force, Navy, or Marine Corps. You’ll be assigned to a new base every 3 years, or so. You’ll be deployed to combat zones for 6-12 months at a time, sometimes with only 72 hours notice. Since you’re serving out your 8-10 year obligation, you don’t get to decline any of these orders.

Your performance at pilot training relative to your peers will determine the order in which you can choose your aircraft. However, the needs of that particular branch of service will determine which aircraft are available when it’s your turn to choose. For example, if you’re ranked 5th in your pilot training class, and there are 5+ fighter slots available, you will have the opportunity to pick one (although it may not be the exact fighter you want). If on the other hand, there are only 3 fighter slots available, your dream of flying fighters may be over forever. As they say, timing is everything.

Air National Guard / Air Force Reserve

The path I wish I’d known about is the Air National Guard and Air Force Reserve. These two organizations are theoretically backups for the Active Duty Air Force, and they’re intended to be a part-time job for most pilots. The tagline you often hear is “one weekend a month, two weeks in the summer,” though as a fighter pilot you’ll have to spend at least one full week per month in your squadron just to maintain your qualifications.

One of the biggest benefits of the Guard and Reserve is that you only apply to the units that you want to join. You can be hired with no military experience (and before signing any military service obligation) to fly the A-10, F-15C, F-16, F-22, or F-35. To see a full list of fighter squadron locations in the Guard and Reserve, check out the MilRecruiter Map.

You will attend the same Undergraduate Pilot Training (UPT) as your active duty peers, but you will have the benefit of knowing that not only will you fly fighters, but you will know exactly which type of fighter and the location of your assigned squadron for the rest of your career. This is critical:

Joining the Guard or Reserve is the only way to guarantee that you’ll get to fly a fighter.

The Guard and Reserve also offer nice pay and benefits, though these work differently than Active Duty. The Guard and Reserve also have a pension for pilots who give at least 20 years of service. Again, this works differently than the Active Duty version.

Earning pilot wings in the Guard or Reserve still obligates you to 10 years of service; however, that service can be part-time. You’ll still end up deploying, though there tends to be a lot more flexibility on when and how often you go. Most Guard and Reserve pilots have other full-time jobs. Airline pilot is by far the most common “other” job, though I’ve heard of anything from lawyer, to entrepreneur, to beach bum. If, on the other hand, you want to work full-time at your Guard or Reserve unit, there will almost always be full-time orders available in most fighter squadrons.

There are pluses and minuses to each path. However, if your ultimate goal in life is to become a fighter pilot, we absolutely recommend choosing the Guard or Reserve path. For more information on the (very different) application processes for these paths, check out our 2-part series here.

Academic Preparation

All US fighter pilots are commissioned officers, which means you must have a college degree. How well you do in that college program will often determine your competitiveness for any pilot training application. The most fundamental and objective input into any of these rankings is your GPA.

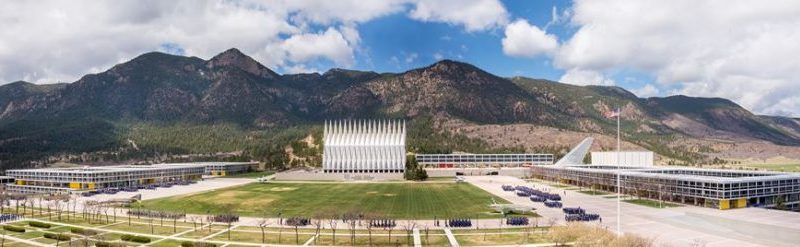

One school of thought says that you should take the easiest classes possible to make sure you get straight As and maximize GPA. At the USAF Academy, one of the most common majors is Management. It’s lovingly (or derisively) referred to as “The M-Train” because so many people hitch a ride to maximize the class rank to effort required ratio. I’m not a huge fan of this mentality, for reasons we’ll discuss in a moment. However, this is a delicate situation.

On a Guard or Reserve hiring board, the value of your GPA is very important. A 3.5 GPA in Business will stand out more favorably than a 2.6 in Engineering. You should choose a degree program in which you can maintain at least a 3.0, though you’re a lot better off keeping your GPA even higher than that.

That said, you need to learn how to handle a challenging academic load at some point. Being a fighter pilot requires a lot of studying throughout your career. It also requires actually absorbing and being able to apply the information you study. If you somehow manage to get to a fighter squadron having never learned how to study, you’re in for a rough life. Taking some classes in high school and college that actually challenge you will help you learn to study. It’s not about English, or Chemistry, or Social Studies now...it’s about weapons specs, tactics, and threat profiles later.

Another reason to choose a more challenging program is that some of the easier college degrees are worthless. We wish everyone reading this a long career of healthy flying, but that doesn’t always work out. If you were to find yourself medically unqualified at some point in the future, a marketable degree will be invaluable. Choose wisely.

Responses