Symptoms of The Pilot Disease Worse Than COVID-19

With COVID-19, our world is facing one of the worst crises in recent history. The virus itself is bad enough, but its economic impacts threaten even longer-term effects. I don’t want to make light of the pandemic, but in the interest of making a point to a bunch of pilots, I’m going to make light of it.

As bad as coronavirus may be, we pilots are susceptible to an even worse disease. This pernicious canker turns otherwise good pilots into useless lumps. It kills promising career progression, brings great shame upon our squadrons, and puts the lives of others at risk. What do we call this horrible pandemic? Copilot Syndrome (or Wingman Syndrome for you fighter types).

Table of Contents

- Signs and Symptoms

- Long-Term Prognosis

- Effective Therapies (Next Week)

- Ineffective Therapies (Next Week)

Signs and Symptoms

If you’re reading BogiDope, you’re probably astute enough that you implicitly understood what I meant when I gave you the name of this syndrome. However, some pilots catch this disease without realizing it, and the symptoms progress so slowly that they fail to come to terms with their condition until it’s too late. As we look at the characteristics of Wingman/Copilot Syndrome, take a few moments for self-inventory to see if you might be infected. (Don’t worry if you are, we’ll discuss the cure later.)

At its heart, Copilot/Wingman Syndrome is apathy, become habit. A pilot with this syndrome probably has decent stick and rudder skills at any given moment. However, his or her overall level of interest in and attention to the big picture, the mission, or aviation overall, is low.

Knowledge

What’s your knowledge level as a pilot? How well do you really know your aircraft’s systems, operating limitations, and characteristics? Can you recite your unit or company’s Tactics, Techniques, and/or Procedures (TTPs) from memory? Can you quickly find references for each piece of your knowledge in your publications?

A victim of Wingman/Copilot Syndrome will dread being asked questions about any of this stuff. He or she knows what it takes to get by from day to day, but won’t be able to provide much detail without digging into pubs. Speaking of the pubs, this person will require extra time to find a reference for anything in those pubs because they’re so unfamiliar.

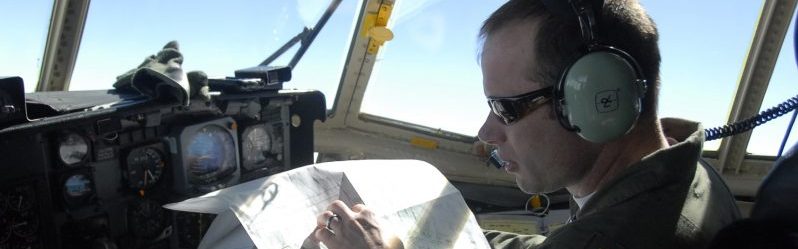

I saw this type of Copilot Syndrome on my very first deployment as a brand-new U-28A copilot supporting Special Operations Forces (SOF) over Afghanistan. My Aircraft Commander (AC) was a nice guy who I enjoyed hanging out with. He’d been around for a while and was slated for Instructor Pilot upgrade when we returned to the States.

Part of the U-28A’s mission is to coordinate all the aircraft in the “stack” supporting a given ground mission. The SOF teams always had A-10s, AH-64s, and/or an AC-130 for Close Air Support (CAS). They would get some combination of U-28A, MC-12W, MQ-1, MQ-9 or civilian contract assets for Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR). There’d usually be an EA-6 or EC-130 for jamming. Finally, most operations also got a pair of F-16s or F-15Es for additional CAS.

Until the Joint Terminal Attack Controller (JTAC) was on the ground, someone had to make sure each of those aircraft got to its assigned position and had its sensor or targeting pod tasked to watch a useful part of the target area. The U-28 had a great sensor of its own, the ability to broadcast and receive sensor feeds, and lots of fancy radios...making the U-28 AC the ideal person to do all of this coordination.

As part of this process, the U-28 AC had to keep track of the weapons that each aircraft had available. When the JTAC first showed up, the U-28 pilot gave him a run-down of the stack, including all the firepower at his disposal.

You’d think that a prerequisite to this job would be knowing what all of that armament was. I’d been a B-1B copilot before joining the U-28 community and was intimately familiar with all manner of weapons. I blithely assumed that any other pilot dealing with combat airpower in support of SOF would have similar knowledge. I was wrong.

One day, on a slow mission without any boots on the ground, this particular AC turned to me and said, “Hey Emet, you were a bomber pilot so you know a lot about weapons, right?”

“Uh, I guess so.”

“Yah...I’m supposed to upgrade to IP pretty soon. Before I do that, I need to have you teach me about that because I’m pretty clueless. I run stacks full of aircraft all the time, but I couldn’t tell you the difference between a GBU-38 and a GBU-12.”

I almost choked on my Gatorade. Here was an Aircraft Commander, in a position of authority over me, leading a crew of people, coordinating a stack for of weapon-carrying aircraft for a poor 20-something-year-old JTAC hiking through the mountains of Afghanistan in the middle of the night while getting shot at...and this AC hadn’t even cared enough to learn about the weapons in his stack.

It turns out that this disease isn’t limited to affecting just wingmen and copilots. Don’t assume that just because you’re an Instructor, Evaluator, Weapons Officer, Squadron Commander, etc. that you are immune.

Mission Planning

Another sign that you might have come down with this syndrome is that your mission planning suffers.

Do you really consider your flight plan’s validity, or do you just assume that your wingman or copilot got everything right? How much conscious thought do you put into your preflight briefing, and how much of it is just reciting standard garbage in case your DO happens to be passing by the briefing room? Have you ever started taxiing without actually looking at and thinking about your destination’s weather and NOTAMs? If you are a copilot or wingman, and your Flight Lead or AC dropped out at the last moment, do you actually know enough about your mission’s plan to run the show?

Don’t get me wrong here...I believe in moderation in all things. I think that Weapon School culture has taken the concepts of mission planning, briefing, and debriefing too far in some cases. The concept of marginal utility applies to this stuff, and at some point you’re better off just stepping to fly, or ending a debrief and going home to your family, than spending another hour (or two or four or eight) talking about it. I believe the key is to find a happy medium.

Let’s look at another story:

I had another buddy in the U-28 whom I love and respect. We’d deployed together many times and flown combat missions together. At one point in our careers I’d been made an Evaluator Pilot (EP) while he was still just an AC. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it shows you where this story is going.

My buddy, let’s call him Steve, had some less-than-stellar performance on a couple missions downrange. At home, people seemed to notice that he just didn’t seem engaged in preparing for flights. A flying squadron is a small place and the commander heard enough about it that he directed me and another EP to give Steve a no-notice checkride. The boss was most concerned about Steve’s mission prep, so the checkride was just that - a tasking to plan a theoretical mission. We both liked Steve and knew that this shouldn’t have been a challenge. We lobbed him a softball...a local mission to a nearby Army base for a training exercise.

We gave him a day’s notice, and he had nothing else scheduled. The next morning, he briefed a mission with decent detail, but we weren’t wowed. We started digging, asking relatively basic questions about his plan and it was obvious that he hadn’t worked that hard on his plan. It shocked me a little, because he knew this was a checkride. However, I was also worried that if he was being so lazy for this, he could be putting people in danger by being even lazier on actual training missions.

That checkride did not end well for Steve.

We had a long talk about why the checkride happened in the first place, and how he thought it had gone. He admitted that he’d gotten complacent and not put enough effort into his flying overall, or this event in particular.

The outcome of the event necessitated we repeat the process a couple of days later. The moment we showed up we knew that it was going to end a lot better. The briefing room was covered in materials, yet professionally and thoughtfully organized. His briefing was far more thorough than we would have expected the first time through, but we appreciated his efforts this time around. We made a point of digging deeper into his plan with follow-on questions, and Steve was able to immediately answer everything...and show the references in his mission planning materials.

Steve obviously passed this second attempt with flying colors. That made the first time around even more disappointing though. He is a great dude and a great pilot. Nothing about his knowledge or skills prevented him from passing the first checkride. His poor performance was entirely due to his attitude...his Copilot Syndrome. He continued to progress in that squadron and flew many more effective combat missions. However, his failure on that first checkride is now a permanent blemish on his record. Whether he aspires to join a Guard or Reserve unit, or work for an airline, he’s going to have to tell this story to potential future employers for the rest of his life. I hate that it has to be that way for him.

Don’t be like Steve. Take a couple minutes to think about your mission planning and consider ways to do better. I’m not saying that you should become that crazy pilot who spends endless hours buried in minutiae, or the Weapons Officer who loves to hear himself talk for hours on end while everyone else in his flight fights to maintain consciousness. However, I want to make sure that you don’t wait for a no-notice checkride or Part 121 line check to be your wakeup call.

Delegation

Another very insidious symptom of Wingman Syndrome is how much you delegate. Are you too good for mission planning? How about attending Instructor Development or other enrichment briefings? How many times during the mission planning process do you allow yourself to be interrupted for very important, official business? How often do you show up to the step desk or gatehouse without having looked over the mission planning products that your wingmen/crew have put together?

I saw this strain of Copilot Syndrome on another checkride. I was tasked to do a regular, old, annual instrument/qualification checkride for Mark (an AC) and Walt (a copilot). Mark showed up to the mission briefing at the absolute last minute. His excuse was, “Hey guys, sorry to be pushing it to the last minute. I just finished up some leave since I’m deploying in two days.”

That squadron was pretty laid-back, and we were extremely busy with deployments, so I didn’t think much of it at first. We all had to take leave when we could. We chatted for a few minutes before I said, “Cool, how about we get started?” Walt (the copilot) looked expectantly at Mark (the AC) and was met by a blank stare.

“Oh, do you want me to brief the mission?” asked Mark.

Hopefully, this question surprises you as much as it did me. Granted, in this particular squadron, it wasn’t uncommon to give a copilot the “opportunity” to brief a mission for his or her professional development. However, the default was always for the AC to brief, and it was Mark’s place to say otherwise.

Wanting things to get moving either way I said, “Unless you want Walt to brief it.”

“Yep, I think that sounds good. Walt, would you like to brief? You could probably use the practice anyway, right?” (Nice, dude. Have the copilot practice something that isn’t even part of his job description on his checkride.)

To his credit, Walt was happy to brief and jumped right into it. Not only was his mission briefing as professional and thorough as I’d have hoped to get from any qualified AC, it quickly became clear to me that Walt had done all of the mission planning. In that squadron, we had a habit of briefing instrument approaches before going flying. When it came time for Mark to brief his approaches, he didn’t even know what airports we were flying to that day.

We flew the checkride and it went okay, but not great. Walt had one “momentary deviation” from standards that could have gone either way. (I think we all have one of those on most checkrides). Mark flew okay, with a few mistakes, but low Situational Awareness throughout the mission.

Walt passed his checkride with a single downgrade for his mistake. It was the sticky sort of thing that I could have also used as an excuse for him to fail the checkride. If anything else had been lacking in his performance (or I was an Evaluator in Air Mobility Command) that one mistake might have done him in. However, he did such a great job with mission planning, briefing, and flying, that he absolutely earned that one mulligan.

It’s one of my greatest regrets as a professional aviator that I didn’t give Mark a failing grade on his checkride. I hammered his scores with several downgrades, but he still passed. The biggest factor in my decision was that he was scheduled to deploy in a couple days. Our squadron was already tapped-out, and there was nobody to replace him. I should have done it anyway. He had an advanced case of Copilot Syndrome. I hope my stern debrief and his ugly Form 8 were enough to cure him.

Not My Problem

Another sure sign of Wingman Syndrome is having a mindset of “I don’t need to know that.” As a Wingman most of your life will consist of keeping lead in sight, and being on the correct radio frequency. You’ll be tempted to not learn the procedures for departing from and returning to your base. You’ll be tempted to not learn the parts of radio calls for directing setups for practice maneuvers. You’ll be tempted to not think about how you’d run a mission briefing...all because that’s not your problem. Right?

That’ll work fine until the day when your flight lead’s aircraft breaks and you have to find your way to the range all by your lonesome. Or maybe your FL had to divert because of fuel issues or maintenance and you’re called upon to speak to your flight’s part of a mission in the debrief.

If you’re afflicted with Wingman Syndrome, you won’t bother paying attention to or thinking through these sorts of things ahead of time. That’s a bad choice.

When I was a T-6A Flight Commander at a UPT base, one of my assigned IPs, Ivan, had come from a heavy community. He’d never flown much close formation, but all T-6A IPs are made 2-Ship Flight Leads no matter what.

Ivan did well enough as a flight lead when everything went to plan. However, I started hearing complaints of issues in his ability to run the show in unexpected situations. One day, he was the IP in the lead aircraft when the formation was required to execute an uncommon arrival procedure. The procedure was clearly outlined in our In-Flight Guide, and we’d all discussed it briefly. However, he’d either not studied it in a long time, or never studied it in much detail. That arrival didn’t go well. The IP in the other aircraft had to get directive, and they still had a tough time executing the procedure without getting in trouble.

Ivan’s Wingman Syndrome manifested as his assumption that he didn’t need to know that arrival. He assumed that if he ended up on it, either the student would know what to do (um, no) or that he’d be in the #2 aircraft and could just follow along.

We had a chat about his overall flight lead skills. He reluctantly agreed that he needed some work. We made sure he got the practice he needed, and he improved as a flight lead. However, he got to the point where he needed help in part because he felt that he didn’t need to bother preparing for every contingency he was likely to face.

Mother May I?

If you find yourself asking for approval or permission, especially when you shouldn’t be, you definitely have a case of Copilot Syndrome.

I was once flying with another pilot, George, on an Aircraft Commander upgrade training ride in a PC-12. That aircraft had a touch & go checklist that had to be completed while rolling down the runway at upwards of 75 knots. (That checklist was not my idea. It was written by C-130 pilots who didn’t understand the difference between a C-130 and a PC-12, but I digress….)

This touch & go checklist had to be completed with at least 2000’ of runway remaining. If not, the procedure was to abort the touch & go. For that aircraft, 2000’ was ample stopping room, even at a maximum landing weight around 9900 lbs.

So, George did a nice landing and called for the touch & go checklist, just like he was supposed to. As the instructor playing stupid copilot I completed the actions required by the checklist, but never verbalized that the checklist was complete.

We cruised past the three board in uncomfortable silence. As the two board approached, the corners of my lips twitched up into a smile. Just before the two board, George looked directly at me and asked, “WTF dude?”

I turned my head halfway toward him with a shit-eating grin on my face, and gave him one more second to make a decision. He didn’t. I took control of the aircraft, planted the throttle firmly in reverse, and hammered on the brakes a little harder than necessary to help make the point. We taxied clear of the runway and had a chat that I’m sure I enjoyed a lot more than he did.

“Emet, WTF?”

“I was just going to ask you the same thing, George.”

“What do you mean? I called for the checklist, you were supposed to complete the checklist.”

“I did though, didn’t I?”

“Well, yes.”

“How do you know?”

“I saw you do it.”

“Okay, so what was the problem?”

“You didn’t verbalize checklist completion.”

“You’re right. What are you supposed to do at the two board if the checklist isn’t complete?”

“Abort.”

“Did you?”

“Well, no. I wasn’t sure if I had to because it’s not that it wasn’t complete it was just that you suck as a copilot.”

“Valid. Were we in a safe position to abort?”

“Yes.”

“Were we in a safe position and configuration to continue?”

“Yes.”

“So, we could have safely executed either option. If (let’s even assume when) you complete AC upgrade, who will be in charge of making the decision, either way, in a similar situation?”

“Uh, me.”

“That’s right! So, why were you looking at me?”

“Oh.”

We’ll get to more on this later, but I believe one of the most important mindsets a pilot can have is “Drive it like you stole it!” If you’re in charge, make the decision! If you’re not in charge, but the person in charge isn’t making a decision, at the very least speak up. Don’t be a “Mother May I?” copilot!