Army Flight School

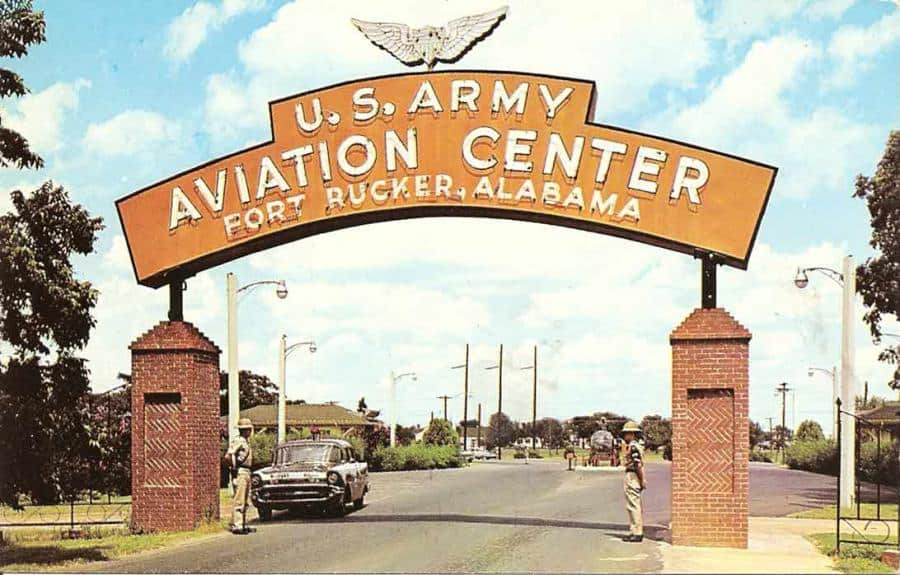

So you did it. You decided whether you’d be a RLO or a WO, you decided which route to take to get there, you earned a flight slot and you moved yourself (and whatever loved ones you bring with you) down to Ft. Rucker in L.A. That’s Lower Alabama, in case you confused it with some other place... And now you "Learn to Fly," as The Foo Fighters so cordially invited you to do (feel free to take a moment and listen to that spectacular anthem, if you'd like. I'll wait...). But make no mistake, this is not anything CLOSE to the final destination, even if it feels like it’s the culmination of years of hard work. It is, in fact, quite the opposite: it’s just the beginning.

But it’s an exciting beginning! Because this one involves the actual flying…after some more of the Officer-related training and the moderately uncomfortable experience that is SERE School. The next two weeks will be a brief overview, chronologically, of the entirety of the Flight School experience. And, given everything that entails, I want you to believe me when I say “brief.” This will be meant to give you an idea of what to expect as far as structure and timelines, but it's hardly more than a glance into the actual meat of the different phases.

So now that your expectations have hopefully been set, welcome to Flight School.

Table of Contents

Basic Officer Leaders Course (BOLC) OR Warrant Officer Basic Course (WOBC)

This four-week course is a logical follow-on to what an Officer has already learned in the process of becoming a RLO or a WO, regardless of the route by which they accomplished that. An administrative note really quick: BOLC/WOBC is CURRENTLY four-weeks long. But that changes regularly. It’s been anywhere from 4-7 weeks. A fair portion of it is simply refreshing and re-testing skills that have been learned and tested in the process of gaining a commission: Land Navigation, Basic Tactics, Weapons Qualification…Army stuff. Soldier stuff. Officer stuff. BUT with a pinch of aviation mixed in. So RLOs and WOs will be learning a lot of the stuff you, the reader, have been learning over the course of this series of articles: the different aircraft and their mission sets, the mission of Army Aviation, as well as basic unit structure in aviation, Combat Vehicle Identification, Combined Arms doctrine (in a VERY bite-sized amount)… Like I said, the basics of officering in Army Aviation.

Most often, immediately following completion of BOLC/WOBC, students will then spend two days (though, for many, it may require a couple more) undergoing Helicopter Overwater Survival Training (HOST), more commonly known as “Dunker.” This involves a morning of academics and then a basic swim/water survival test (in uniform, so practice this if you’re a weak swimmer), the successful completion of which culminates in the actual “ditch” iterations on day two.

There are videos all over the place about this that are far more informative than trying to describe it, but in short: you strap into a box that simulates the fuselage of each Army aircraft, it gets lowered into water and flipped upside down and you have to then successfully escape and swim free without aid. And you’ll then do it all while blindfolded. Some people are incredibly intimidated by this. Don’t be…the instructors WANT you to succeed, so they’ll help you figure it out. Beyond that, it’s actually a ton of fun.

After completing Dunker, students often encounter a “bubble,” or a wait period between classes, while they’re awaiting SERE. Such bubbles can be encountered regularly throughout Flight School as students complete one training syllabus and await their next training window. These bubbles will often be filled with additional duties, details or whatever else will keep them somewhat engaged while Uncle Sam keeps paying them. The longer the bubble, the more likely that “filler-job” will be something that is 8-10 hours/day, 5 days/week. So be prepared for this.

Survive, Evade, Resist, Escape (SERE)

This is the course that is the most daunting to many, up front, when beginning the process of becoming an Aviator. Sure, people often wonder whether they’ll be any good on the controls of a helicopter - hoping they’ll just “be a natural” but worrying the opposite will be the case. Others stress about whether they’ll do well in the rigorous circuit of aviation academics. But the rumors swirling around this course are many and they are varied. Which tracks…the majority of what’s covered in the course is classified. And all of these rumors assure one that they will be uncomfortable. Often VERY uncomfortable. It’s not so much a concern for whether they’ll pass the course…it’s more a concern for how much pain they’ll need to endure BEFORE they pass the course.

And with good reason! SERE School does, indeed, get pretty uncomfortable at some points. But it’s like any uncomfortable thing; it’s uncomfortable and then it ends. So don’t sweat it. Just do the thing. And don’t give up.

As to the nuts and bolts of the class, well…it’s not my place to divulge any of that, frankly. Like I said…it’s classified stuff. So I’ll leave it to an actual Army Public Affairs-approved message related to SERE to give you any information that’s been approved for release to the public at large. Yes, there are many places where you can get more information, but much of that is likely out-of-date, skewed by the author’s desire to make themselves seem like a Spartan at Thermopylae, or flat-out false. So if you’re interested in the basic construct and a general outline of what the course covers, follow this link.

Be aware that various training logjams or circumstances HAVE led to students completing SERE after they’ve already completed all of their flight training. This makes absolutely no sense to me, but it happens occasionally. Don’t expect it, but just know that there’s a small possibility it could happen. I don’t know of ANYONE who would wish that on themselves or the ones they love, though, so if it happens to you…I’m very sorry.

I will say no more.