Air Force Career Progression – Officer

We’re going to discuss career progression today. As a former Active Duty pilot, I’ll admit I don’t love this topic.

You have to understand: I’m a pilot. I didn’t join the Air Force to sit at a desk pushing paper or sending emails. When I graduated from the Air Force Academy in 2004 and got to shake President Bush’s hand, all I said to him was “Thank you, sir,” and our class motto: “Ready for War!”

I went on to fight his war for several years, and I loved it!

You’d think that a pilot could focus on nothing but that…nothing but being an expert at employing Air Power against the enemies of the United States and the military would, in turn, take care of that pilot and his or her family. Like it or not, there’s more to it than that.

If you want the option of continuing to serve in the military for a full career, and if you want your family to have access to the amazing benefits and retirement that accompany that career, you have to make sure you obey the military’s instructions on how to be a good officer. (The Guard and Reserves are generally better about this, but each unit requires its pilots to play the same game to varying degrees.)

Thankfully, the career progression game is not cosmic. It’s possible to do what the military expects of you while still focusing on the parts of the job you actually care about.

I’m living proof that it’s possible to look really good in the eyes of the military without having to sacrifice too much of your time or attention on the stuff that you deem unimportant. You see, the Air Force loved me. My performance reports were embarrassing. The Air Force offered to send me to the Norwegian Command and Staff College for my Intermediate Developmental Education. They only have one slot for that school each year, and just the prestige from attending that program would have all but guaranteed me squadron command and promotion to O-6.

I didn’t have to sacrifice my identity as a pilot to achieve any of that though. I was an Evaluator Pilot in two aircraft, and an Instructor Pilot in three. I flew 312 combat missions all over the world. I checked every box the Air Force ever asked for but did so with disdain toward everything that tried to take me away from flying.

In hindsight, my disdain wasn’t all that productive. I hope you’ll do better than me and go with efficient indifference instead. However, today I’m going to tell you exactly how to have a fantastic military career, that preserves all your promotion options, without giving up on what’s important. We’re going to focus on progression for an Active Duty Air Force pilot. The same principles will apply in the Guard and Reserves. Some units stretch out timelines or don’t require you to accomplish all of these steps. However, it’s worth you understanding what your Active Duty counterparts are dealing with for context.

You’ll notice that this article is broken up into two separate categories of career progression: one for officer, and one for pilot. It turns out that every military pilot has to manage his or her progression on each of these paths. One path involves flying aircraft, while the other one involves being an officer. Yes, being an officer (or warrant officer) comes into play as a military pilot. However, most of what the military defines as “officership” involves writing reports, attending staff meetings, and doing other office work. We’re going to look at these two paths separately, starting on the officer side.

Table of Contents

- Officer Accessions

- Specialty Training

- First Jobs

- Company Grade Officer (CGO) Leadership Opportunities

- Professional Military Education (PME)

- Leaving the Squadron

- PME for Field Grade Officers (FGOs)

- Master’s Degrees

- Staff

- After Staff

- Command

- Guard and Reserve Differences

- Discussing Your Goals With Your Commander

- Up Next

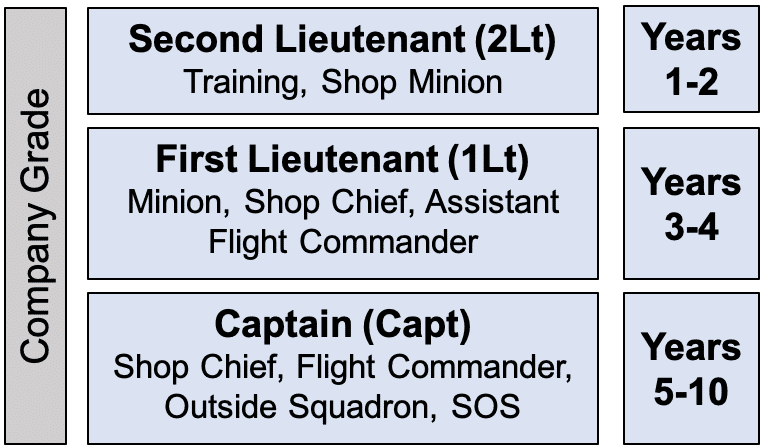

For our visual learners, the first few sections of our career progression discussion cover this part of your career:

Officer Accessions

A military pilot’s career starts at a commissioning source. For many, this is the USAF Academy or ROTC. For pilots smart enough to go directly to the Guard or Reserve, this will mean OTS (now called TFOT). The honest truth is that it doesn’t matter which source you come from. From here on out, all that matters is how good of a person and a pilot you are.

There are always rumors that one group (especially Academy grads) favors their own unfairly. In my experience, most of the people who get really worked up over this are people getting overlooked for reasons other than their commissioning source…and they just don’t realize it. Don’t be that guy or gal.

How many times in college did someone ask or really care about the sports or clubs you participated in during high school? I bet your answer is close to zero. The same thing applies to military officers. People care that you can do your job well and that you’re enjoyable to be around. It doesn’t matter whether you were the coolest kid ever or a total loser in your past life. It doesn’t have any bearing on what you’re doing now.

I think most people feel some loyalty to their college and the people they attended it with. However, serving in the military gives you far more meaningful experiences to bond over than drunken dorm parties or late-night class projects. Focus on where you are now and the people you are with.

Specialty Training

On the day you graduate from college or TFOT you will be the most useless person in the entire US military. Sure, you’ll have some fancy degree, but you will have zero skills usable in employing Air Power against America’s enemies. You’ll need to go to some type of training, which means UPT for most BogiDope readers.

We’ll discuss this in more detail when we talk about career progression from the pilot perspective. (We’ve also written about UPT in our series describing all three phases of training, and our series on Winning UPT. After UPT graduation, you’ll probably go to SERE and Water Survival. Check out our post on these schools for details.)

From an officer development perspective, you should focus on learning your new skills during this training. If you’re the Senior Ranking Officer (SRO) in any given course, you may be placed in charge of your classmates. Try to do a good job as a leader, but realize that your performance will not be formally documented. It may play into your flight commander ranking in UPT, but it’s a secondary consideration.

Sometimes, scheduling constraints will mean you have to wait as long as a year between commissioning and starting UPT. If that’s the case you’ll likely be sent to a random base to fill a random role for that year. Sometimes called “casual status” or just APT for “awaiting pilot training,” this year can be good or bad.

If you’re lucky you’ll either get a fun and interesting job with some good people. You may even be placed in charge of some enlisted troops and get to learn how to deal with them – a skill that most Air Force pilots miss out on.

Another desirable APT job is one where your boss doesn’t really have much use for you. There will be plenty of time to go to the gym and find a copy of the T-6 aircraft manual and AETCMAN 11-248 to start studying for UPT.

A slightly less desirable APT assignment would involve working for a mean and/or demanding boss who doesn’t understand the concept of “balance” in life. He or she may give you lots of boring projects and expect completion on unrealistic timelines. If you get this, just make the best of it.

UPT lasts exactly one year in the Air Force, though Navy pilot training has been known to take as long as two. With all the other early pilot career progression steps we mentioned, it’s not unrealistic to think that you could already be a First Lieutenant / Lieutenant JG when you get to your first operational squadron.

First Jobs

If you look in the regulations for your aircraft (the “11-2” series pubs) you will find a paragraph that states something to the effect of: “It is forbidden for new pilots to have any job, other than being a pilot, for the first 6 (or 12) months in a new aircraft.” This is absolutely a great sentiment and the USAF would be better if this happened. Unfortunately, every squadron commander I ever worked for knowingly violated this regulation. His or her justification was always that the squadron wasn’t even staffed at full strength and in order to keep the circus running, even 2Lts had to help.

This means that as soon as you report to your new squadron you’re going to be assigned a job. Your squadron has many “shops” or departments to include: scheduling, mobility (deployment), plans (long-term scheduling), weapons and/or tactics, training, standardization and evaluation, admin/awards and decorations, etc.

The Air Force also has a position called Executive Officer. Don’t get this confused with other military branches where the Executive Officer (abbreviated XO) is second in command of a boat or unit. In the Air Force, and “Exec” has the office symbol of CCE and is basically an overpaid secretary/administrative assistant to the commander.

Each of these shops exists because it’s necessary for running a combat squadron and you’ll need to learn what each of them does as part of your job.

You’ll start out as a clueless minion in your shop. Over time, you’ll figure out what your shop needs to be doing, and you’ll start receiving assignments. You may get transferred from shop to shop to shop during your first couple of years. Although this could happen because you’re weird or you smell bad, it’s probably a good thing. You want experience in as many different shops as you can get if you hope to eventually be a Squadron Commander in charge of them all.

Company Grade Officer (CGO) Leadership Opportunities

Your first real leadership opportunity as a Company Grade Officer (CGO – ranks Second Lieutenant through Captain) will be as a Shop Chief for one of these departments. Some of the other military branches give the Air Force a hard time about not giving its officers’ leadership opportunities early enough in their careers. Those people simply don’t understand how the Air Force works. Shop Chief is absolutely a leadership position, and you’re vulnerable for the position as a 1Lt.

You’ll potentially be in charge of officers, enlisted Airmen, and even civilians. You’ll answer to your Squadron Operations Officer (DO) and/or Commander (Sq/CC). Your ability to effectively lead your people will directly affect your squadron’s ability to go to war. It’s a lot of responsibility for someone in his or her early 20s.

Shop assignments are functional areas that keep a squadron running. Although a Shop Chief has authority over the people in the shop, this is not a command job, per se. Each Air Force Squadron is also divided up into three or more “Flights.” Each Flight has a Commander (Flt/CC) who reports directly to the Squadron Commander. This person is usually a Captain (O-3), though I’ve seen unique circumstances where Flight Commanders held ranks from 1Lt through Colonel. (The O-6 Flight Commanders were in my wife’s Dental Squadrons. It’s a weird world.) Each Flight Commander has an Assistant, sometimes abbreviated AFC.

The Flight Commander is the actual link in the chain of command between a line pilot and the Sq/CC. The Flt/CC is responsible for writing a pilot’s annual Officer Performance Report (OPR) and other care & feeding kinds of activities. That doesn’t mean a Shop Chief can’t also care about the welfare of the people in his or her shop, but those responsibilities are only formally assigned to the Flight Commander.

It’s possible to become an AFC or Flt/CC without having ever been a Shop Chief. It’s also possible to go from Shop Chief to Flt/CC. It doesn’t matter much which way you do this. Your records will show you progressing to new jobs of increasing responsibility throughout your career, which is all that matters.

Professional Military Education (PME)

The Air Force places a great deal of emphasis on Professional Military Education, or PME. As a Captain, you need to complete Squadron Officer School (SOS). The in-residence version of this course is held at Maxwell AFB, AL, and it lasts 5-8 weeks, depending on who’s in charge and how they’ve tried to adjust the syllabus lately.

There is also a correspondence (aka online) version of SOS. An officer used to be expected to complete the correspondence version of a PME course before the chain of command would even consider sending him or her in-residence. Thankfully, the Air Force has realized what a waste of tax dollars that mentality was and has largely squashed it. The AF has gone to great lengths to make in-residence SOS available to all Captains. You should only need to do the correspondence version if unusual circumstances have prevented you from attending in person.

Officially, it isn’t supposed to matter how you get SOS done. That’s mostly true. On a promotion board, there is usually enough to differentiate between two people so nobody ever looks at which version of SOS an officer did. However, if two people looked nearly identical, having gone in-residence could theoretically make a difference.

The in-residence version of SOS also makes you eligible to compete for Distinguished Graduate (DG) honors. I believe it’s a very negative characteristic of the Air Force, but getting DG is a huge deal for your career. It places you on a special, accelerated career path. It will get you better assignments and more positive attention from your chain of command. If you aspire to high rank and a long career, in-residence SOS is important because it gives you a shot at that classification.

When I went to SOS, the people who wanted it the most ended up not getting it. Those who did seemed to be more experienced officers who had a lot to share with the class. They contributed actively in class and did a good job on all their assignments because that is their personal standard, but they didn’t obsess over things. They made sure to enjoy themselves and the break from real life.

Overall, don’t get too wrapped up about trying to become DG at SOS. There are other ways to get onto the shiny penny career path. Just try your best while maintaining balance in life and things will work out.

Leaving the Squadron

Once you’ve been a Shop Chief and/or Flight Commander, you’ve just about topped-out on useful career progression within your squadron. The Squadron DO has a few assistants (ADOs), usually a job for Majors or Lt Cols. This is a good move up from Shop Chief or Flt/CC, but not mandatory.

Even if you spend time as an ADO, you eventually need to get a job outside the squadron. There are usually jobs at the “Group” level (one level higher than the squadron) for executive officers, weapons and tactics, and standardization and evaluation. Some groups may also have positions for other functional areas. Your Wing Commander has his or her own executive officers along with a safety office, a plans shop, and other departments.

You need to move on to one of those jobs. As a Captain or Major you’ll start all over as a higher-level minion. The Air Force relies on the jobs throughout your career to expose you to increasingly larger spans of responsibility. It’s important for you to gain perspective at organizational levels higher than an ops squadron.

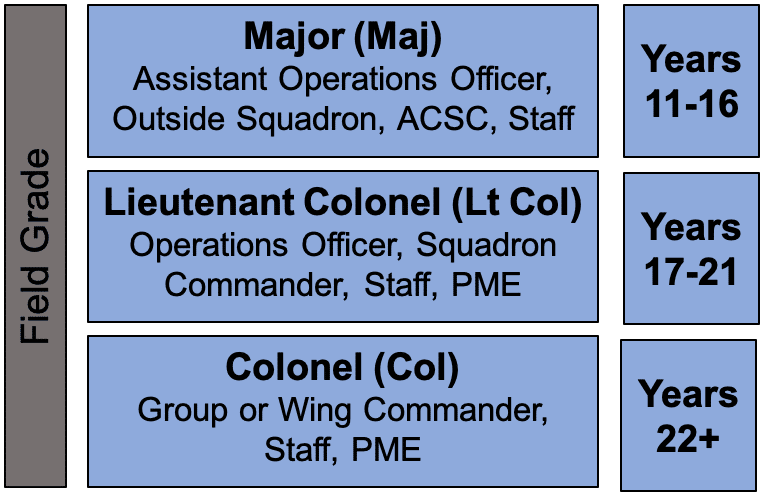

This is the second phase of your career as an officer is summarized in this chart:

PME for Field Grade Officers (FGOs)

As a Field Grade Officer (FGO – ranks Major through Colonel) you’re expected to complete the next level of PME, called Air Command and Staff College (ACSC). Like SOS, ACSC can be completed in person or by correspondence. The difference is that not everyone gets to attend in-residence, so it becomes a competition.

You’ll work as an ADO or in a Group or Wing job while you wait for your shot at ACSC. Although you’re officially not required to complete the correspondence version first, you may feel some pressure to do so. ACSC in correspondence is a nightmare right now. It has several self-paced courses, but there are also four live/proctored courses that are only offered a few times per year. If you don’t complete the self-paced courses in time to register for the next section of the proctored course, you’ll be stuck doing nothing until the next opportunity. Best case, it takes seven months to complete ACSC by correspondence.

Personally, I recommend signing up for ACSC and knocking it out as soon as possible, meaning the day you find out that you’ve been selected for promotion to Major. It will be a pain in the neck but it’s better to have it done and not need it, than the other way around.

The other reason to have it done early is that ACSC isn’t the only option for in-residence PME for Majors (also known as Intermediate Developmental Education, or IDE). Each year, the Air Force publishes a list of special programs you can apply for that count as IDE. These range from attending the IDE-equivalent at other services’ staff colleges, to internships at DARPA, to legislative fellows programs at Harvard, to Foreign Area Officer training through the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) and the Defense Language Institute (DLI), and more.

I’m told that ACSC in residence is a fun and relaxing year; however, most of these other competitive IDE programs are also unique and enjoyable. They’re at least slightly better for your career because they make you stand out when compared with your peers. Some of these programs are considered extremely prestigious and have an effect like SOS DG, but amplified. In many cases, you’re required to complete ACSC by correspondence in order for the unique program to count as IDE. It’s far better to already have that done than to try and squeeze in ACSC by correspondence while you’re attending Harvard, trying to learn Chinese at DLI, or trying to match grunts drink for drink at the Marine Corps Command and Staff College.

Master’s Degrees

Before we get on to post-IDE assignments, we need to take a moment to discuss graduate school. Like it or not, a long-term Air Force officer must earn a Master’s Degree. It used to be that this was a prerequisite for making Major. Thankfully, the pilot shortage has helped kill that requirement. It may be possible to make Lt Col without a Master’s, but I wouldn’t risk it. You won’t make Colonel without one.

This means that you have to find time in the first 6-8 years of your Air Force career to do grad school. If you’re lucky, you can get one of the special IDE programs that also grants you a Master’s Degree. However, those programs are pretty competitive, so I wouldn’t count on it.

The Air Force offers an alternate version of ACSC in correspondence called the Online Masters Program (OLMP). If you don’t want to pay for grad school and you see the utility in combining this task with getting your IDE done, this could be a good option. Realize that this course demands even more than the regular correspondence version of ACSC. You should expect it to take 1.5 – 2 years to finish.

I think the OLMP is a fairly rare choice. There are plenty of universities with online programs these days. Many cater to military students and charge exactly as much as the Air Force Tuition Assistance program pays. I chose an MS in Human Factors Psychology through the University of Idaho, in part because it seemed like a rigorous course that didn’t require a thesis. However, I have some friends who went all-out and did an MS in Astronautical Engineering with a thesis.

Officially, the Air Force couldn’t care less what school you go to or what your degree is in. It’s merely a box to check in your record. While this is true for a promotion board, your degree choice could be important later in life. If you aspire to be a test pilot, astronaut, or anything else technical, you should do a degree in mathematics, a hard science, or engineering. If you aspire to one of the special IDE programs related to politics or becoming a Foreign Area Officer (FAO,) you should study Political Science or International Affairs.

It’s also worth noting that future employers pay attention to the what and where of your Master’s Degree later in life. When I went to Mentor training at my airline, someone very high up in the company told us that having a degree from a more prestigious school and/or a technical degree is a plus on your application.

It may be tempting to get a box-checking degree in “military studies” from a no-name, online-only university. However, if you can stand to put in a little more effort, I say it’s worth pursuing a challenging degree from a school that at least has a physical campus and a name that people recognize (for good reasons).

If you’re paying attention to the length of each section in this article, you’ll notice that I’ve spent far more time discussing education than I have on actual military leadership jobs. We’ll discuss more of the leadership opportunities you get as a pilot in Part 2 of this post. However, I’ll admit that some of the other services’ criticism of the Air Force is valid. Some of this is simply based on the structure of how the Air Force fights. Other than crew positions on some of our aircraft (load masters, flight engineers, gunners, boom operators, etc.) most combat Air Power is employed by officers. It’s exceedingly difficult for a Marine or Army ground commander to comprehend this difference (Using crayons to illustrate your points helps!). However, for better or for worse, it is true that the Air Force relies heavily on education for a lot of its officer development.

The sooner an Air Force officer can get each step of his or her education done, the better. It frees you up to focus on things that really matter (like flying or having a life/family). It’s also very noticeable to your commanding officers if you have your ducks in a row early in your career. Whether they do it consciously or not, they’ll favor you for awards and assignments if you have all of these important boxes checked as early as possible. Get it done, then forget about it and move on!

Staff

Having completed Air Command and Staff College, the Air Force prefers you to spend your next assignment serving on a staff.

There is a lot of variety among staffs and staff tours, and there is a sort of hierarchy to the prestige of these assignments. The top tier is The Air Staff, working for The Chief at the Pentagon, or perhaps working directly for the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs. Below that are DOD-level combatant command (COCOM) staffs like US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) or European Command (EUCOM). Next is Air Force major commands (MAJCOMs) like Air Combat Command (ACC) or Pacific Air Forces (PACAF).

Your staff assignment is based upon your overall record and your performance at your IDE program. If you aspire to high rank, you should shoot for the most prestigious staff possible. There isn’t enough room for everyone on the Air Staff, so don’t be offended if you don’t get it. As always, do the best with what you have.

The enjoyment of staff tours is very much a mixed bag. Sometimes you’ll work for a great boss who realizes that your family has sacrificed a lot. You’ll get to work on interesting, meaningful projects and go home every night at a reasonable hour. Unfortunately, some staff jobs place you under the command of people who just don’t get it. They’ll expect you to work excessively long hours. They may not understand what your background brings to the fight and will use you on projects that have nothing to do with your specialty. They may send you TDY (on business trips) a lot, or even let you be deployed for 6-12 months of your staff tour. I hope you get a good staff tour. If not, just remember that it will be over someday.

After Staff

Once your staff tour is done, you have some decisions to make. If you’re highly competitive for command, you’ll follow a track that we’ll discuss in the next section. If you’re only somewhat competitive, or not competitive at all, you’ll probably have the option of staying on staff or going back to a Wing.

If you choose to stay in staff jobs, it should be based on the fact that you used your time there to network and have a good follow-on job lined up. Ideally, this will put you at a good base, in a job you enjoy, with some friends. It’s frequently possible to target jobs that will put you near extended family too. This is usually a play for family Quality of Life, more than career advancement. If you can make that work, I think this is a great option.

If you decide to go back to flying, you’ll have several possibilities. You could go back to your Major Weapon System (MWS) in an operational unit. You could also go back to your aircraft’s schoolhouse as an Instructor Pilot. This could let you return to flying an aircraft you love, at a location you know, while being less vulnerable for deployments…at least for a while. You’ll also have the option of going to a UPT base or other more generic training job.

In any of these assignments, you’ll primarily be looking at a job as an ADO in a flying squadron, working somewhere on base at the Group or Wing level. You’ll be eligible for jobs like Chief of Group Standardization and Evaluation (OGV) or Wing Chief of Plans. These aren’t always the most thrilling jobs, but you’ll get to fly on the side. You could do a lot worse. If you’re leaning toward leaving Active Duty and possibly trying for a UPT IP job in the Reserves, an assignment to a UPT base would be a strong choice.

If you’re not competitive for command, this could be the end of the line for your Active Duty career. It’s usually possible to find a way to stick around for a full 20 years and earn a retirement.

It’s possible that you won’t be competitive for command in your MWS, but you could have that opportunity at a UPT or other training base. I had two outstanding Squadron Commanders when I was an IP at Laughlin. One was an F-15C pilot and his command was his final assignment. Another was an F-16 pilot. He did a great job with his command and ended up moving on to higher-level assignments. Both seemed to thoroughly enjoy their time as Squadron Commanders. Don’t be afraid to choose this path if you aspire to command and won’t get it in your MWS community.

Command

Speaking of command, this is where the Air Force wants officers to end up after IDE and staff. The “ideal” career path involves spending some time as an Operations Officer (DO). This is a good way to get back into your aircraft, get a refresher on life in a squadron after the staff, and studying how to be a commander. If there aren’t enough DO jobs available at your base, the Wing Chief of Safety position is usually considered an equally competitive stepping stone.

In general, the Air Force tries to put you in charge of a squadron where you weren’t the DO. If there are two squadrons on a base flying the same type of aircraft, it’s not unusual for the two DOs to take command of the opposite squadrons at the same time. In the Air Force, squadron command is usually a 2-year assignment. If you do well and you’re on track for further promotions, you’ll be looking at Senior Developmental Education (SDE). You may have to wait for that by spending some time as a Deputy Group Commander or going back to a staff position. The Air Force needs to push so many officers through the squadron command job that it’s extremely rare to command a squadron more than once.

We could go into great detail on officer career progression past this point, but I think we’ve covered enough for now. If you get to that point, there will be no shortage of Colonels and Generals happy to discuss your options with you. You’ll also have figured out by then whether you have the potential to progress farther or not.

Many pilots consider squadron command to be the pinnacle of a flying career. You’ll be at or near 20 years by the time you finish that job, and unless you really want to pursue higher-level rank and staff jobs, this is a great time to retire.

Although the Air Force puts a tremendous amount of emphasis on squadron command, I recommend not using it, or any other rank or title, as your ultimate career goal. There’s a surprising amount of subjectivity in deciding who gets these good deals and it’s not healthy to base your happiness on something well beyond your span of control. One of my best squadron commanders continuously told us that each person has to define “success” for him or herself. If you base your definitions on things you can control, letting any titles or ranks serve as a bonus, you’re guaranteed to be happy with your career.

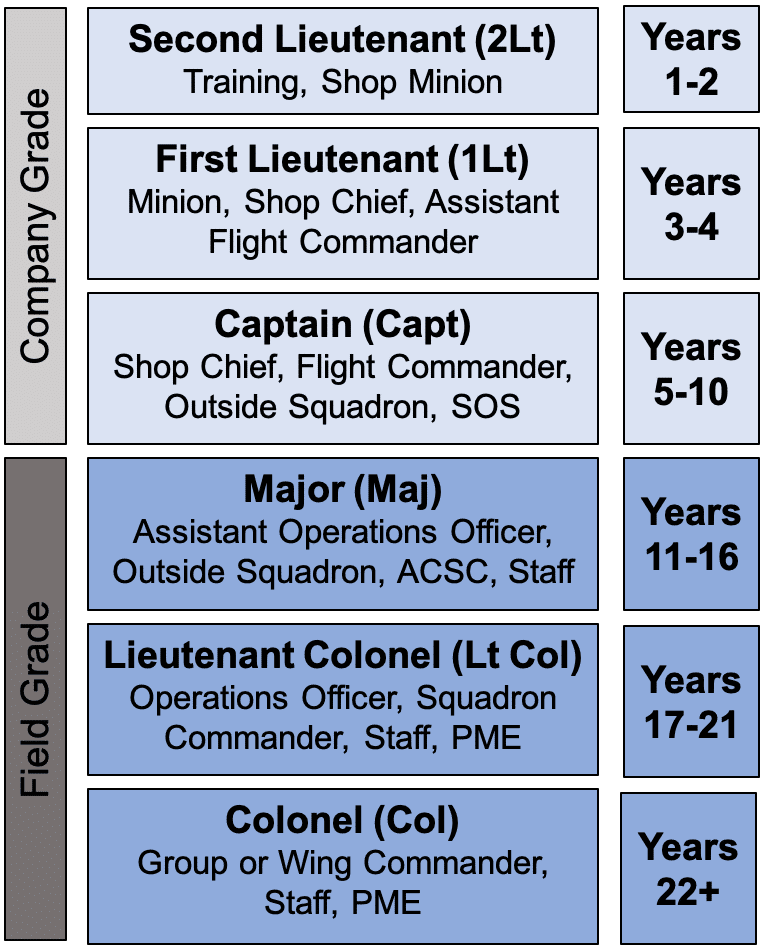

Put it all together, and an Air Force officer’s career progression will probably look something like this:

Guard and Reserve Differences

We’ve just covered the basics of officer progression for an Active Duty Air Force pilot. Most of this applies to the Guard and Reserve, to varying degrees. The main difference is that the timelines can get extended.

One of the best parts of a Guard or Reserve unit is that a pilot can spend an entire career there. However, this means there isn’t a constant stream of people moving up in rank and job, leaving shoes for you to fill. You may have to wait until someone high up retires, and leaves some room for people to move up to new jobs or take promotions before you get a chance to do the same. This is a great deal!

On Active Duty, everyone is constantly churning through a rat race of career progression. In the Guard or Reserve, you have more opportunities to enjoy where you are, master your current job, and enjoy flying your aircraft. Revel in and take advantage of this!

You’ll still have the opportunity to move around to different jobs both within your squadron, and at the Group, Wing, or even staff level. Frequently, those jobs require a full-time worker so you’ll only be able to do them if you take a few years of full-time orders. There’s nothing wrong with this, though you have to be careful you don’t exceed your limits for taking military leave from your civilian job.

You’re free to complete your PME courses by correspondence. There are seats allocated at each of these courses for Guard and Reserve personnel, and the Air Force actually has a tough time finding volunteers to fill them sometimes. If you’d like to take a couple of months to attend SOS, or a year to do ACSC, be sure to let your leadership know early so they can plan ahead and work on getting you a slot.

The long-term nature of membership in a Guard or Reserve unit means that there’s an almost airline-like seniority system. You’ll know who’s in line ahead of you for jobs like squadron command. If you aspire to something like that, the best thing you can do is be fantastic at your job and maintain a good relationship with the people in your community. As long as you do, your leadership will be motivated to help make sure you get your shot at your dream job.

Thankfully, unlike Active Duty, the Guard and Reserve is also happy to have you stick around and just fly, even if you don’t aspire to a high rank or fancy command jobs. Anecdotally, the majority of Guard and Reserve pilots are drawn to this track.

If you aspire to staff jobs or earning General’s stars, you can do that here as well. There are part- and full-time staff jobs available to Guard and Reserve pilots. You may be able to do some in your state, while others will require moving. You can serve on the headquarters staff for the ANG, AFRES, or in Guard or Reserve positions on staffs where most of your coworkers are Active Duty.

Most states have at least one General Officer serving as Adjutant General (state-level commander). The highest-level commanders in the Guard and Reserve are 4-star Generals. Reaching those levels generally requires enough full-time service that it would be difficult to accomplish as an airline pilot. However, if that’s what you aspire to, it’s absolutely a possibility.

Discussing Your Goals With Your Commander

No matter what your career goals may be, it’s important to make sure your commander knows about them!

As a brand-new pilot, this includes your Flight Commander, but you should also speak directly with your Squadron Commander about it. Most Squadron Commanders are happy to talk about career development with you. It’s best to talk to the boss’s executive officer or secretary and get an official meeting scheduled on his or her calendar.

No matter whom you’re speaking with about career progression, you need to do it tactfully. As a brand new Lieutenant, your #1 concern should be learning how to employ your aircraft well. You’re supposed to spend almost all of your time worrying about that, and very little time thinking about 5-10 years in your future. You should make sure that people know you as a hard worker who knows his or her stuff and flies the aircraft well before you broach the subject of career progression with anyone.

Once you start having those conversations, you should not jump directly to what you want in the future. You should humbly and genuinely ask for feedback on how you’re performing in your current job. It’s okay to bring up your future goals but do so carefully. At first, you should just mention your goals in terms of asking what else you can do in your current job to make yourself eligible for those opportunities.

You should wait until you’ve earned some of your advanced pilot qualifications and some credibility within your community before you start bringing up specific assignments or opportunities that you want to pursue. If you’re open to a lot of possibilities this can wait, while if you want something specific or special, you may need to start discussing it earlier in your career. (Expect some upcoming articles that help illustrate this.)

On some level, your boss wants and needs to hear that you plan to become an expert on your aircraft, complete IDE and a staff assignment, and come back to be a Squadron Commander. It’s okay to want something other than that, but I recommend always emphasizing how your pursuit of other/special opportunities will keep you competitive for traditional career progression in your community.

Some Squadron (or Group or Wing) commanders will actually be offended and confused if you say that you want to pursue an opportunity that will take you out of your primary community. The first time one of my buddies got picked up for the U-2, he was so enthusiastic about it that I had an application filled-out the next day. I was just about to send it to my Squadron Commander when word came down from the Wing Commander that he wasn’t going to release any more pilots for BS like the U-2 program. That is a stupid mentality that has more negative effects for the Air Force overall than it could possibly have positive effects for any specific Wing, but that’s a Commander’s prerogative. I ended up (regretfully) not even submitting my application because I didn’t see any use in making people angry.

Don’t be too worried if you face obstacles like this. My career worked out very well anyway. I excelled within my community and that Wing and got some other special opportunities. I also ended up teaching at a UPT base where I was largely out of reach of my MWS community. I could have submitted a U-2 application from there and been safe from an unfriendly Wing Commander’s wrath. If you find your path blocked now, wait a little while and you might find a way to make things work after all.

Talking to your boss about your career goals requires some tact, but it’s important to do it. You can’t get what you want unless you ask for it. Air Force Squadron Commanders fly less than anyone in their unit because their primary job is taking care of their people. Your boss will be thrilled if he or she can help you get the assignment of your dreams. Give him or her the opportunity to help you by expressing your goals.

Up Next

We just looked at the officership side of career progression for an Air Force pilot up through the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. This feels like a lot, though it’s honestly just an overview. Don’t be afraid to find a mentor who can elaborate on each of these sections and help put them into context for your goals. Like it or not, you need to pay attention to this part of your career progression and check the appropriate boxes when you can.

However, this is only part of your job. You also need to take care of career progression as a pilot. That topic is broad enough that we’re saving it for another week. Be on the lookout for Part 2 in the near future.

Image Credits:

The feature image for this post is from a video at: https://www.dvidshub.net/video/712178/leadership-and-development-course.

The APT student FOD check is from: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/5315178/laughlin-airmen-earn-air-force-level-awards.

Mobility line picture: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/5813699/training.

The picture of SOS students is from: https://www.dvidshub.net/video/714011/cde-squadron-officer-school-craig-smith.

The photo of the CSAF briefing ACSC is from: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/4699048/csaf-shares-squadron-revitalization-vision-command-insights-with-acsc.

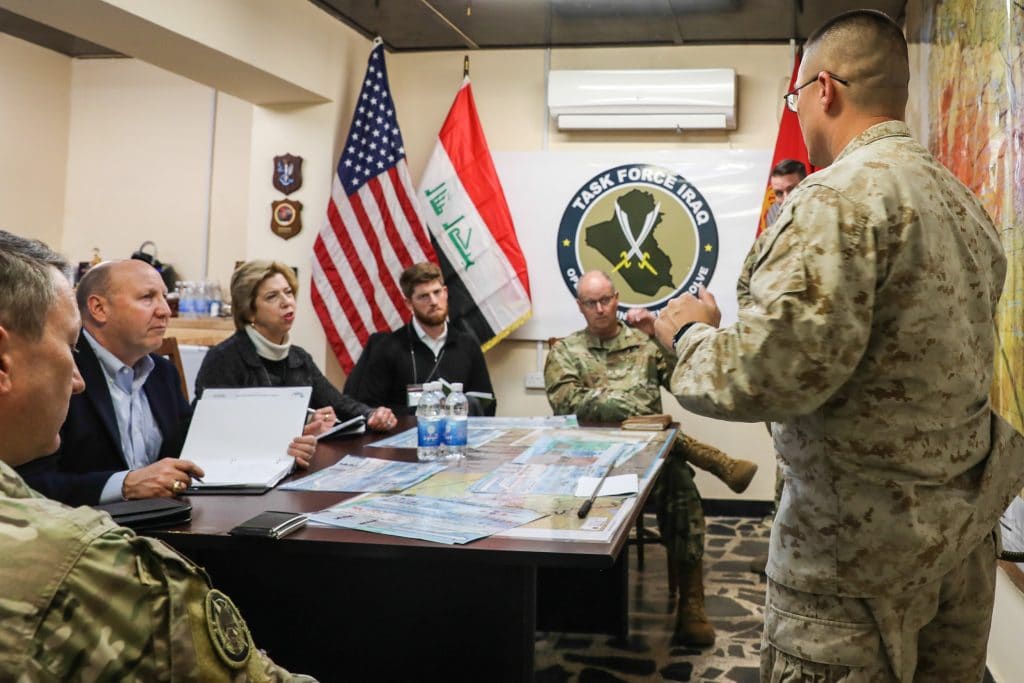

The staff meeting in Iraq is from: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/5920955/honorable-ellen-m-lord-meets-key-staff-members-union-iii-iraq.

The assumption of command photo came from: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/6085539/new-commander-takes-charge-492nd-fighter-squadron.

The shot of Gen Lengyel is from: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/6056009/gen-lengyel-guam-national-guard-troop-visit.

The mentoring session is from: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/5674402/angs-outstanding-first-sergeant-year-1st-sgt-rachel-l-landegent.