Active Duty How-To: Olmsted Scholar

Within the military, there are some opportunities that seem so amazing that they must be too good to be true. I’m excited to tell you about one of those today. We’re going to look at the Olmsted Scholarship – an all-expense-paid 3-year assignment that involves learning a language and then earning a master’s degree in a country where that language is spoken. Although I’ll be writing this from the context of an Air Force officer, you should note that this program is also available to officers in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard.

I continue to assert that the Guard and Reserve represent the Ultimate Military Pilot Career Path for most people; however, the Olmsted Scholar program is one of the few good deals you can only get on Active Duty.

For this article, I got to interview my friend, Lt Col Michael “Slam” Baird. We’ll get to more details on him shortly, but for starters, he’s an Olmsted Scholar now serving as the Defense Attache at the US Embassy in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. Before we talk about him though, we’ll talk about the man who started this program in the first place.

Table of Contents

- General Olmsted

- Slam’s Background

- Scholarship Basics

- After the Scholarship

- How to Compete

- Conclusion

General Olmsted

Major General George Olmsted had a very distinguished career. He graduated with distinction from Westpoint and ended up playing several important roles in World War II. After the war, he excelled in a career as a civilian businessman. This took him back to China for extended periods of time.

Through both of his careers, General Olmsted realized the power that comes from understanding a variety of languages and cultures. He felt the military lacked this expertise and wanted to change that. Instead of writing a new regulation or offering his hopes and prayers, General Olmsted left $40M to start the Olmsted Foundation that runs this scholarship program.

On a personal level, I believe that General Olmsted is 100% correct. I believe that our military is woefully short on skill and knowledge of foreign language, culture, and politics. I’m fluent in Russian language and culture, having spent almost two years there on a mission trip. Russia is playing us like a fiddle and exerting significant influence throughout the rest of the world. If our country’s leaders had an actual understanding of Russian language and culture, they’d be better prepared to see what’s going on and do something about it.

On a similar note, we’ve been embroiled in Afghanistan for nearly two decades. (Didn’t a wise man once say “Never get involved in a land war in Asia”?) If we’d already had a decent level of understanding and expertise of the languages, peoples, religions, and cultures at play in that region in 2001, we could have decisively ended President Bush’s Global War on Terrorism in short order, and without the loss of life or extreme expenses we’ve incurred.

The Olmsted Scholarship provides what could be the most important type of education a senior military officer can have in our global geopolitical environment. An officer interested in doing big things in a military career should do everything in his or her power to earn a spot in this program.

Slam’s Background

Now that we know who founded the scholarship, let’s talk about one of the scholars. I want you to know his background to give the context of his comments, but I’m also just proud of what he’s done and enjoy taking the opportunity to brag about him.

I met Slam when we were both brand new U-28A pilots at the 319th Special Operations Squadron at Hurlburt Field, FL. He’d come there from an assignment flying the F-16 while I’d been flying the B-1. No, neither of us volunteered for that assignment. This happened under a program called TAMI-21. We’re both very happy with how our careers ended up, though we were not pleased with ole TAMI at the time. The famous pilot band, Dos Gringos, wrote a song about the program that captured our feelings perfectly. (Warning: extreme vulgarity and language.)

Slam had studied some French in high school and enjoyed learning languages. At first, the 319th didn’t have much work for us new guys so Slam snuck into lots of spare spots in classes at the Joint Special Operations University on base. He also talked someone into letting him take an intensive French language course with the 6th SOS. In one of the JSOU courses, he met an officer whose husband had been an Olmsted Scholar. She explained the program to Slam and he immediately knew it was what he wanted to do.

He applied to the program 3 years in a row, and with much help from several other Olmsted Scholars he met along the way, he got picked up on his last chance. After 10 months of studying the Ukrainian language at the Defense Language Institute (DLI) in Washington, DC, Slam ended up studying in Lviv, Ukraine. He happened to be in the country when protests on Kyiv’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti started a revolution in the country and got to watch the whole thing first-hand.

After completing his studies and an intervening year in Washington, DC, Slam was assigned to the US Embassy in Ukraine as the Air Attache. This was a fantastic assignment in a country that was very interested in working with him. His counterparts were friendly and welcoming, and he got numerous opportunities to hang out with them on Ukrainian Air Force bases. (Their ongoing war with Russia may have had a small influence on their attitude.)When the USSR split up, Ukraine ended up with a lot of fantastic military hardware, but 20+ years of limited resources for training and general neglect left the Ukrainian Armed Forces woefully unprepared for combat with their large and aggressive neighbor. Slam is most proud of his role in helping to facilitate the Clear Sky 2018 Air-to-Air Exercise, in which the California Air National Guard’s 144th Fighter Wing sent their F-15Cs and pilots to train with the Ukrainians.

You may remember that California’s Lt Col Seth “Jethro” Nehring, and Ukraine’s Col Ivan Petrenko, were killed in a Su-27 incentive ride mishap during that exercise. It was a tragedy that hit hard for all involved, but it is a testament to the professionalism and dedication of the US and Ukrainian pilots, as well as an indicator of the importance of the mission, that they were able to absorb the impact of that blow and continue on with training missions and the final Large Force Engagement (LFE) exercise. It is worth noting that California’s Air National Guard has been partnered with Ukraine, as part of the State Partnership Program (SPP), since 1993 and so the relationships run deep. Jethro and a couple of other guys have been involved in Ukraine for years and years.

Anyhow, Slam must have done a decent job as the Air Attache in Ukraine because he was subsequently promoted to full-up Defense Attache in the Kyrgyz Republic, after another intervening year in DC. You may recall that the US was unceremoniously booted from our base in Bishkek a few years ago. Russia never liked us having a base on their doorstep, and Kyrgyzstan’s neighbor to the east (China) also wasn’t particularly enthused. Now that US presence is significantly reduced, Slam has a much more challenging environment to deal with on this assignment.

Slam was about as happy to leave the F-16 as I was to leave the B-1, but like Andy Dufresne in The Shawshank Redemption, he too came out clean on the other side. If he sticks around on Active Duty, he may eventually be competitive for general’s stars (if he does his Senior Developmental Education in-correspondence, of course). He could also easily go to an airline after reaching retirement eligibility in a few years, and/or he might be able to find a nice Guard unit to fly the Viper with again. However, with his experience, he’ll likely now have access to a variety of fun and fascinating corporate jobs as well. All of these opportunities are his, thanks in part to the Olmsted Scholarship. Let’s talk more about how that works.

Scholarship Basics

Every year, the Olmsted Foundation awards scholarships to 10-15 officers from each branch of the military. This scholarship covers up to a full year of language training, followed by two years in a master’s degree program in a foreign country.

General Olmsted wanted the program to be challenging – to teach officers how to learn and adapt, fully immersed in an unfamiliar culture. The Foundation wants to know that you have a genuine interest in foreign affairs and/or languages, but actual skills in a foreign language are not required. In fact, if you do know other languages, note that they absolutely will not send you to a country in which your skills apply. No matter what, you’ll be starting from scratch with the language you study in this program. (If that sounds horrible, this program is not for you. Go ahead and click this link to read the latest Karlie Kloss news. If this sounds like an exciting challenge, then you should be very excited to finish this article.)

You submit the Olmsted application through your military chain of command, which can be a challenge in and of itself. If your application actually makes it to the Olmsted Foundation’s selection board, the competition gets even more fierce. If you’re lucky enough, you’ll get invited to an interview (that usually happens as a video chat these days to save money.)

Although this is as serious an interview as you’ll ever get, it has some unique aspects. Part of the application process involves researching master’s degree programs you’re interested in pursuing. While the Foundation prefers you study political or social science, history, or international affairs, there aren’t many firm restrictions. We’ll see shortly that part of making your application competitive is successfully arguing the benefits of whatever programs you choose.

Much of your “interview” involves the members of the board (all past Olmsted Scholars themselves) engaging you in an open discussion about the programs you’re considering. They’ll bring up points you may not have thought about yet. They may suggest alternate courses for you to look at. They’re not afraid to suggest that some programs and locations may be better if you’re bringing a spouse and/or children with you on this adventure. (And yes, the Olmsted Foundation is happy for you to bring your family!)

If you get awarded a scholarship, you get some time to finalize a list of 10 programs you would like to do. The rank order of these programs isn’t all that important, and you should not include any as “throw-away COAs.” You need to be ready, willing, and even excited for every program on your list. Once you’re awarded a scholarship, it’s up to you to apply to and get accepted by one of the programs you listed.

Slam’s list had a wide variety of programs on it. He put a program in Brazil because Portuguese is a Romance language related to French. He also put down Indonesia, a country that comprises thousands of islands, lies on the Strait of Malacca, is on China’s doorstep, and has the highest Muslim population of any country on the planet.

Slam’s overall career goals were to do Olmsted, do an embassy tour, and then come back to Hurlburt Field. The mission of the 6th SOS is Foreign Internal Defense, one of the Core Activities of USSOCOM. It’s the ideal assignment for a graduated Olmsted Scholar. He noticed that the 6th SOS was doing a lot of training with Slavic-speaking former-Soviet countries, which is part of the reason he put Ukraine on his list.

Slam ended up choosing a Ukrainian language program in Lviv for some very specific reasons that we’ll talk about shortly. He initially planned to attend Ivan Franko University in Lviv. As he’d actually already completed a master’s degree in International Relations, he figured he’d do the same degree, just in a different language and from a different perspective.

However, on Slam’s orientation visit to Ukraine, the administrators at Ivan Franko wanted him to spend a full year taking nothing but Ukrainian language classes before starting his degree program. This would have involved starting from scratch with language training, even though he was speaking Ukrainian with the administrators as they discussed his options. He felt that he’d be better off pushing himself without the extra year of language study.

Instead of spending a year rehashing the basics, Slam ended up opting to attend the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv. This university is funded largely by diaspora populations in the US and Canada. Their administrators were much more on board with what he was trying to do and recommended he try a degree in history.

Ten months of language study at DLI is absolutely world-class language training. However, for a language as difficult as Ukrainian, it’s not enough to get anyone up to graduate school-level language skills. Slam’s classes were conducted in Ukrainian, but at least 50% of the reading was in Russian. The two languages are closely related, but different enough that even if you’re up to a middle-school reading level in one, you’d be hard-pressed to do graduate-level work in the other.

In any case, UCU’s graduate history program was focused more on “how to be a historian” and thesis-related historical research, for which Slam was not prepared. After a year of struggling to keep up (in two languages) with a degree on how to be an academic, Slam ended up negotiating another plan. He took a variety of actual history and language courses, watched a revolution (more on this in a moment), and finished his time there without earning a degree.

It turns out that roughly 50% of Olmsted Scholars end up not completing their degree programs. (If you think Ukrainian is tough, try going to graduate school in Chinese with only 10 months of language training!) While a degree is preferred, The Foundation is more interested in the overall experience the Scholars get.

Surprisingly, this wasn’t a problem for the Air Force either. The reality is that the Air Force will not recommend you for this program unless you are already “promotable.” The overall plan is that you’ll do Olmsted, do a Foreign Area Officer (FAO) “payback” tour, then come back to the “normal” leadership track for your specialty (i.e.Operations Officer (DO) to Squadron Commander for pilots). They want you to be competitive for promotion to O-5 at what used to be called “below the zone,” and then continue with Air War College, a staff tour, and all the other wonderful things involved with staying in the Air Force instead of getting a seniority number at an airline.

One of the fundamental steps to being competitive for all of that is having a master’s degree. As such, the Air Force won’t even consider you for Olmsted unless you have already completed a master’s. Since you already have that degree before you do Olmsted, it’s not a big deal if you don’t finish the degree during your scholarship.

This isn’t necessarily the case for other services though. The Air Force only considers officers from the 7-10 year point so that Olmsted can count as their Intermediate Developmental Education (IDE). This effectively means that all USAF Olmsted Scholars have at least met their Major’s board and have been selected for promotion, even if they haven’t yet pinned on.

Other services try to send their officers much earlier in their careers. These services don’t have the time to send their officers to a second master’s degree program after Olmsted, so this is their one shot. As such, they have to choose programs and languages carefully. (One helpful point is that some foreign degree programs are conducted in English, even though they’re in countries where English is not an official or even a common language.)

We’ll move on to bigger-picture career considerations shortly. However, there are a few more things worth mentioning about the Scholarship experience itself.

It is probably not an exaggeration to say that Slam’s experience in Ukraine was life-changing. Living fully immersed in another culture, and getting to know people and learn about their country from the inside, is enlightening enough. A front seat to a world-shaking revolution is on a whole different level. When it kicked off in November and December of 2013, he essentially just told his professors, “Um, I’m going to take some time and go check that out.” And he left. He figured that he’d learn a lot more talking to people on the Maidan than writing ancient history essays in the bowels of some library.

In any case, essentially the entire student body and the professors were taking turns traveling the 6 hours or so to Kyiv to spend several weeks at a time on the Maidan in support of the protests. Sadly, one of the young lecturers in the History Department, Bohdan Solchanyk, was killed by a sniper in the final days before the former Ukrainian President fled the country. Do yourself a favor and watch the Netflix documentary, Winter on Fire, to get a feel for what it felt like to observe the revolution from the inside.

(Note: Slam emphasized over and over that he was present within the physical boundaries of the Maidan protests infrequently, and then only as an observer, never as an actual participant. He deliberately took pains to avoid providing fodder for the blatantly false Russian narrative that the US was somehow responsible for the protests).

(On a personal note: Slam and I would feel remiss if we didn’t mention that our buddy and former fellow U-28 pilot, Nolan Peterson, met up with Slam in Ukraine and covered the revolution as a member of the press. For a while he was the only American reporting the ground truth about what was going on there. He’s done some amazing journalism over the past few years. We love his work and hope you’ll stop by his website to take a look at some of it!)

As an Olmsted Scholar, you write a report about your experiences each year. (We’ll see shortly why these reports are extremely important.) This minimal chore (intended to serve as a road map of lessons-learned for the lucky scholar following in your footsteps) is about all you have to do to justify your activities while you’re there. It also helps the Olmsted Foundation account for the yearly travel stipend you are provided with as part of the scholarship. Excuse me? What was that? Did you say travel stipend? Yes indeed. You are given an additional stipend specifically for travel! Let me say that again; you are paid extra money and must accurately account for exactly how you spent it on travel in your country of study AND in the region!

It is probably also worth noting that Slam hasn’t regularly worn an Air Force uniform since 2012 (aside from a 6-month stint at the Pentagon). When I asked him if I should refer people with questions to his Air Force email, he laughed. He hasn’t had access to his af.mil e-mail address in years. (If you want to contact him, go through his LinkedIn profile.) I hope these last details portray the fact that this program frees you from a lot of the rigidity and administrivia of regular military service. It’s demanding in its own right, but it’s definitely a fun and different way to serve your country as a military officer.

After the Scholarship

The Air Force counts the Olmsted Scholarship as your IDE. Also, when you finish the program you’re designated as a Foreign Area Officer (Aka: FAO. They’ve gone back to this title after spending several years using other titles to include: International, Regional, and/or Political Affairs Specialist…IAS, RAS, and PAS). FAO becomes a secondary Air Force Specialty Code (AFSC) in addition to your regular 11X (pilot) one.

The Air Force has done a surprisingly good job of realizing how important these skills are, and they actually take care of their FAOs. After Olmsted, you’ll do an FAO-related tour…probably at an embassy or as a country specialist on some staff. Then, you’ll go back to your primary AFSC and fly. Hopefully, you’ll check the boxes on DO and Squadron Commander before moving on as I mentioned earlier. Ideally, you’re supposed to alternate assignments between pilot jobs and FAO jobs. (Slam is on his second FAO tour in a row due to some unique circumstances.)

During our conversation, Slam made attache jobs sound fascinating. As the senior-most US defense official in the country, Slam represents the Secretary of Defense and works directly for the US Ambassador, the CENTCOM Commander, and the Director of DIA. As our country’s primary interface with the host country’s military, Slam is encouraged to develop relationships as much as possible. Though that’s tough in Kyrgyzstan right now, it made for some great times in Ukraine. He wears a civilian suit most days, he’ll wear Service or Mess Dress to represent the US Military at an official function, and if he’s going to hang out with a bunch of pilots for the day, he’ll throw on the ole flight suit and just be another crew dawg.

I hope reading this has you excited enough that you’ve already elbowed the pilot in the cubicle next to you and vomited all the details you just read. If so, you should start working on your application immediately. This process is different than anything you’ve ever encountered, and you will not succeed unless you know some of the keys that we’re going to look at next.

How to Compete

The Olmsted Foundation website lists the basic requirements for their scholarship; however, that only scratches the surface.

Your respective military branch will publish its own guidance on applying for this program, and you need to religiously follow those instructions. The Air Force does this in the form of a Personnel Services Delivery Memorandum, or PSDM. Unfortunately, this document gets published so late every year that if you haven’t already started on your application by the time you see the PSDM, you’re going to be extremely rushed.

Slam recommends searching around to get a copy of the PSDM from last year and starting on an application as if nothing will change. Chances are that any changes will be minor, and this could give you an extra 364 days (I guess 365 this year) to polish your app.

I mentioned that Slam applied to the Olmsted program three times before getting accepted. This will probably happen to you as well, so don’t let it get you down. This program is highly sought-after and the competition is fierce.

Many Wing Commanders won’t even forward your application to the Air Force level if they don’t think it’s strong enough. That’s obnoxious, but it’s also reality. This is what happened to Slam the first time. On his second try, his application made it to the Air Force level but didn’t compete well enough to move on. It wasn’t until his third year that his application actually made it to the Olmsted Foundation.

In a way, this was a blessing though. He learned from his mistakes and was able to present an eye-watering polished application on his third try. Put yourself in the shoes of a Wing Commander. On one side of your desk is an Olmsted application that has been continuously honed over the course of three years. The grammar, spelling, and formatting are perfect. The officer’s activities have been focused on linguistic, political, and culture-related projects. He or she probably even got something like “Perfect for Olmsted” in the push line of an annual performance report or two. It’s also obvious that this candidate has spoken to a lot of past Olmsted Scholars and has a good idea of what to expect in the program.

On the other side of your desk is an application that was obviously not started until after PSDM was published. The officer is an otherwise strong candidate who has done a lot of great work. However, the application feels rushed and unpolished. There are little formatting annoyances throughout the application. Though the officer has a strong record, little there is especially focused on language or culture. It’s obvious that this candidate’s research of the program is only superficial.

Which one are you more likely to send on?

Although it’s important to start on the application before the next PSDM comes out, you actually need to start preparing long before you reach your 7-year mark.

Olmsted is a graduate degree program, so you need to take the GRE for any school to accept you. If you want to do well on that exam, you’re best off doing at least a little studying. If you don’t do well the first time you take it, you may want to study and take it again. All of this requires time. You don’t want to send your Wing Commander an application that says “GRE score pending,” or worse, “I expect my GRE score to improve on a retake.” GRE scores are typically accepted for up to seven years, so you could take the exam during your 3rd year as an officer and the scores would be valid for your full Olmsted application window.

Many of the services that we discussed in our article on AFOQT prep can also be used to study for the GRE. Your military branch will use your GRE score as a differentiator when comparing your application to your peers, so you need to put as much time and effort as necessary into doing well on it.

Since you’re going to be learning languages, your service will also want to know your score on the Defense Language Aptitude Battery (DLAB) as part of your Olmsted application. The DLAB is a unique exam that looks at exactly what it describes – your ability to learn new languages. You can only take it twice in your military career, so you should try to do well on it. There are some online study resources, though I’m not going to discuss them in detail here. You can rest assured that your DLAB score will also serve as a differentiator on Olmsted applications.

The other reason for doing well on the DLAB is that your score can dictate what languages DLI will let you study. They have minimum thresholds for each language they offer. If your DLAB score isn’t high enough, they won’t let you learn the language. This could cause problems if the Olmsted Foundation offered you a scholarship expecting you to go to Korea or China.

Since the Air Force’s policies require you to be competitive for promotion after Olmsted, you absolutely must have your master’s degree completed before you apply. Although the Air Force is trying to institute a policy that officers don’t have to complete Professional Military Education (PME) in correspondence before doing it in residence, the sad reality is that you’ll be more competitive for Olmsted if you’ve enrolled in, if not completed, ACSC before you apply. You’ll have to do ACSC in-correspondence at some point in any case, as its completion is required for the Olmsted experience to count as in-residence IDE. (It would have sucked if Slam had to skip the revolution to do ACSC discussion posts back in his apartment, because he didn’t bother to get IDE done before he arrived in Ukraine.)

It is also beneficial to demonstrate proficiency in some language as part of your application. I’m a big fan of learning languages, and speak a few. I promise that no matter how smart you are, you cannot pick up language skills overnight. If you’re interested in even possibly applying for the Olmsted Scholarship, you need to be studying a language right now. Your base education office and library probably have a variety of free language learning resources just collecting dust on their shelves. You may be able to take language courses in your community, at a local college, or online.

While I was on Active Duty, I spent several years in the Air Force’s Language Enabled Airman Program (LEAP). It’s a fantastic program that sets you up with live online language classes for free every week. It can help you build your language skills and really impresses your bosses on quarterly awards packages and officer performance reports. Although Slam became an Olmsted Scholar as LEAP was just getting started, he thinks that it would be a great thing to be able to list on your Olmsted application.

I’d recommend you choose your language carefully. On one hand, you want one that you can handle learning primarily through self-study. It’s a lot easier to learn Spanish through self-study than Finnish or Mongolian.

Slam had a DLPT score of 2/2+ in French on his Olmsted application. This is a great score, especially for someone with no formal French education after high school on his records. I’d shoot for a DLPT score of at least a 2/2 for the primary language on my Olmsted scholarship application, though the higher the score the better.

While it might be tempting to choose an “easy” language to study on your own, I don’t believe that should be the end of the story. Slam noted that learning any language is difficult, and you’ll always do better with it if you have a strong personal desire to visit that place and meet those people. If your language study feels like “work” you’re never going to do enough of it to get good. You need to be able to get excited about the language you’re studying.

Personally, I’d also consider trying to differentiate myself for the Olmsted Scholarship by studying a less-common language. Can you imagine how many applications they get from people who speak French, German, or Spanish? That doesn’t give them much to differentiate on. I’d consider studying Icelandic, Basque, Indonesian, or something else that just sounds interesting and unique. I’d choose a place that I was interested in (and capable of) visiting on my own before I submitted my application. If I were writing an essay for an Olmsted Scholarship, I’d want to be able to include something like:

“Learning Cambodian has been extremely challenging while serving full-time as a U-28 pilot, but that made it all the more rewarding when I got to travel to that country last year. I was able to go way beyond the typical tourist experience. I visited places and got to know people on a level that would never have been possible if I’d showed up not speaking the language.”

Be careful though. Slam emphasized the point that Olmsted will likely not send you anywhere that you’ve already studied. If your application says that you speak Fijian, they’re not going to send you to Fiji.

Although we’ve covered a lot of application advice so far, I consider it to be elementary-level stuff. Let’s cover something absolutely critical:

You need to do some serious research on the program itself before you submit your application. Anybody, including you, can set up a login for the Olmsted Foundation website. Remember those trip reports that every Olmsted Scholar has to write every year? Once you have a login, you get access to all of them. You absolutely must scour every report for each of the areas you may be interested in going.

First off, the Foundation doesn’t like sending a person to a school that had an Olmsted Scholar in the past. They want everyone to get a brand-new experience. Second, past reports are treasure troves of insight on issues in a given country that might help you figure out what programs you should consider.

This ended up making all the difference for Slam. It turns out that Ukraine is a complicated place. The vast majority of her citizens know and speak both Ukrainian and Russian. However, people in the capital, Kyiv, communicate mostly in Russian, while the use of Ukrainian is more dominant in the western part of the country where Lviv is the biggest city. Several past Olmsted scholars had signed up to learn Ukrainian, but chosen programs in Kyiv. They arrived to find that while the education program was officially in Ukrainian, class discussions and the majority of their interactions around town were in Russian. Bummer.

Every single one of these Scholars recommended that if someone wanted to actually study Ukrainian, he or she should study in Lviv. Apparently, Slam was the first applicant to pick up on that. During his interview, the board was very impressed by the fact that he knew about the subtleties of where Ukrainian was spoken and what programs would actually allow him to use that language. They likely recognized this as great research, effort, and discernment on his part…and perhaps it played a part in him receiving the Scholarship.

Another reason to read past reports is that you can find out who you should ask for advice and mentoring. I cannot emphasize enough how critical this is. Slam even went so far as to state his belief that no officer has ever been selected for the Olmsted Scholarship without getting help and advice from past Scholars.

If you’re lucky, you already know an Olmsted Scholar who can start mentoring you right now. If not, it’s not that big an issue. Just get that login to the Olmsted Foundation website and start reading reports from past scholars. You need to be doing this research anyway to figure out where you might want to go, and where you shouldn’t ask for because it’s been done before. Each report has contact information for the officer who wrote it. Slam says that you should not hesitate to cold call or email any of them.

Slam feels a “debt of gratitude” for the opportunity that he had to become an Olmsted Scholar. It has changed the course of his life. He wants to help others get an experience as awesome as he got. When people write him, he’s more than happy to answer questions, share his application materials and notes, and look over yours. (The only thing he won’t give you is his essay. That really needs to be in your own voice and he feels he’d be doing you a disservice by influencing that.)

Slam believes that most other Olmsted Scholars feel exactly the same way. He even went so far as to postulate that a polite, concise email to retired General John Abizaid, Commander, US Central Command (and now Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia) may get a reply. Please, don’t bombard him with requests though! Start with people who sound like they might be a little less busy first. I don’t know about you, but I’m impressed that the people who went through this program are such passionate evangelists for it.

It almost goes without saying, but your research on the countries you’re considering shouldn’t stop with Olmsted Scholar reports. You should also be at least conversant on the history of and current geopolitical issues in every country on your list. With as many options as you’re required to provide, this represents a lot of work. This is just another reason to start studying now!

Conclusion

The Olmsted Scholarship is an outstanding opportunity. It’s exciting, challenging, and gives you skills that are critical to our national defense. I think you should consider applying if you’re at all interested in staying on Active Duty for the long-term. I think it’s also a great career path for any officer trying to keep options open after he or she leaves the military.

The Olmsted Scholars are a passionate community of people more than happy to help you prepare your own application. If you’re interested in this program, you must find some past Scholars to help mentor you through the application process.

If I were interested in applying for this program, here are the steps I’d take:

- Start studying a language. Choose one that I’d like to visit, but not one that I want excluded from my list of possible Olmsted Scholarship locations. A person who finds languages challenging might need to choose an easier one. As a person with an affinity for learning languages, I’d choose something unique and possibly more challenging.

- Take the DLPT for my language each year. This will help me gauge my process and know how competitive I am. (The Air Force will actually pay you extra money each month if you score above a given level on certain languages.)

- Study for and complete the DLAB. My minimum acceptable score would be 90-100. However, in the interest of competing well, I’d try for much higher.

- Once I had a DLPT score of at least 1/1 and a decent DLAB score, I’d apply for the LEAP program. Ideally, I’d still be enrolled in LEAP on the day I’m awarded an Olmsted Scholarship.

- Start studying geopolitics on my own. I wouldn’t dare showing up to an Olmsted Scholarship interview unless I could hit the high points on the last 50-100 years of a country’s history and cover a variety of current topics. Realistically, this is a lifelong pursuit, and a skill that will serve an Olmsted Scholar well in the future.

- Study for and take the GRE…as many times as necessary to get a good score. This ensures eligibility for Olmsted degree programs down the line, but it also helps me compete against my peers.

- Complete a master’s degree. It can be in anything, though the Olmsted Foundation would probably prefer to see something along the lines of international relations, history, and social or political science.

- Complete my rank-appropriate PME. This means enrolling in ACSC by correspondence the moment my selection to Major is announced.

- Start reading reports from past Scholars on the Olmsted Foundation website. I’d focus on the places I’m most interested in attending.

- Start forming relationships with past Olmsted Scholars. If there are a few years before I can apply, I’d just express interest and ask for general advice. As the application window approaches, I’d ask for any sample application materials they’re willing to offer. Ideally, one or more of them would help me review and fine-tune my application package.

- I’d volunteer for any type of foreign language- or culture-related project in my unit. I’d try to get those activities mentioned in my official records any way possible. (Most Flight Commanders are desperate for anything decent to write in your annual performance report. There’s almost always room for an entire bullet on Olmsted-relevant activities.)

- Apply for the Olmsted Scholarship, every year, for years 7-10. If (or more likely when) I fail the first couple times, stay upbeat, thank my mentors for help, and work hard to improve my application for the next year.

I know this seems like a lot, but I believe that most things worth doing take a lot of work. Honestly, this is manageable if you’re passionate about language, culture, and geopolitics.

Unfortunately, even if you try your hardest the chances of earning an Olmsted Scholarship aren’t great. Don’t let that get you down though! If you do the math, you’ll see that there are far more embassy and staff jobs that need good people than there are Olmsted Scholars. The Air Force has other pathways that allow a far greater number of officers to do programs that qualify them as FAOs in lieu of traditional IDE. If you’ve worked hard to make yourself competitive for Olmsted, you’ll also be highly competitive for these other paths to becoming a FAO. Many of them even involve time studying language and culture in other countries.

No matter how you get there, I agree with General Olmsted that FAO skills are both critical and lacking in our military. We need hard-working, motivated people like you to pursue this path and help us do a better job of working and cooperating with our allies. If you’d love to make this part of your future, don’t hesitate to reach out to Slam!

Thanks for reading and до побачення!

Image Credits:

The Eagle taxiing past Ukrainian Su-27s at Clear Sky 2018 is from: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/4805777/clear-sky-2018.

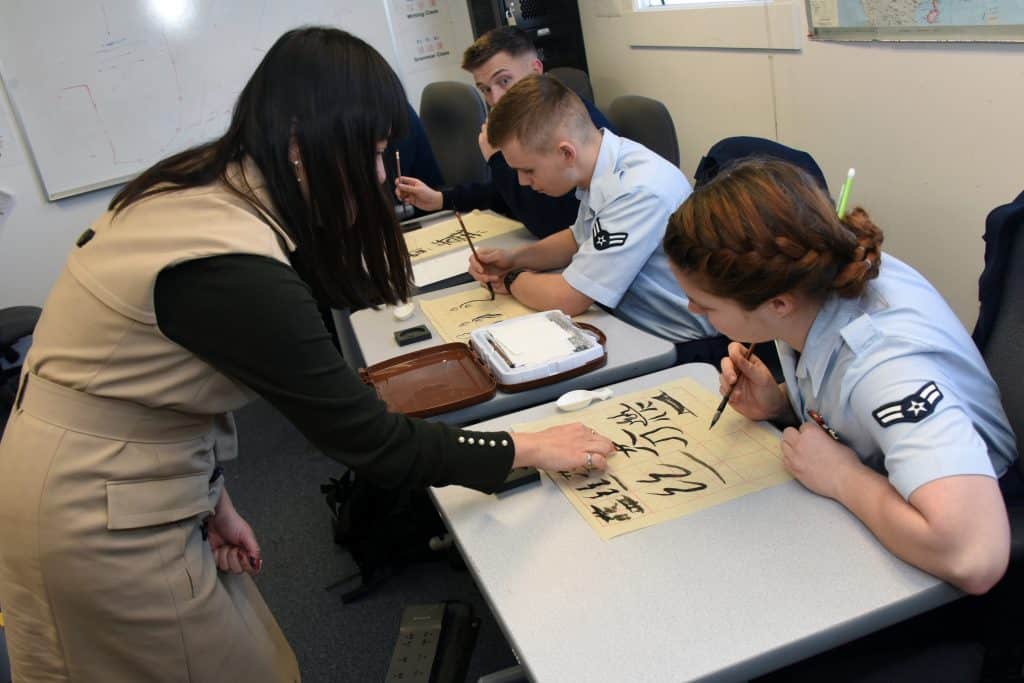

The shot of A1Cs doing Chinese calligraphy is from: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/4355826/learning-chinese-calligraphy-benefits-language-study.

The picture of the UCU campus is from the Ukrainian Catholic Education Foundation website: https://ucef.org/about/.

Slam provided all the other pictures for this post.