Ideal Military Pilot Career Path – Making it Happen – Part 2

Welcome back. This is the second part of a discussion on what I consider to be the ideal career path for a military pilot. If you haven’t already, I recommend reading Part 1 first.

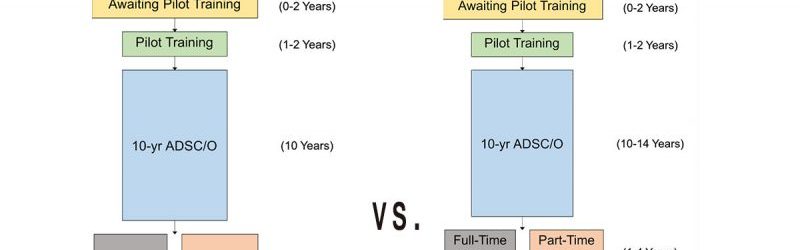

Here’s the summary of what that path looks like:

By leaving active duty as soon as you can, you get an all-important seniority number at a major airline sooner, rather than later. You’re a red-blooded American patriot, but you’re just smart enough that you don’t want to give up a government pension if you don’t have to. No worries: just join the reserves when you leave active duty and continue until you reach 20 years of total service. You get to continue your fulfilling service, you get healthcare, you get a pension, you get airline-level pay for the majority of your flying…and you don’t have to sacrifice your seniority number to make all this happen. Boom! Best of both worlds.

The (Guard and) Reserves are an interesting thing. They offer a wide variety of ways to serve, and I’m confident that you can make one of them work for your family if you choose to pursue this career path. Although I’ve studied this, the system is complex enough that even I don’t know all the options out there. Adam Uhan has suggested that we do a TPN Podcast episode discussing some of these options. I’m looking forward to that, but I’ll try to at least give you an overview of some options now. After that we’ll look at how to land the job you want, and cover a couple other considerations that may sway your thinking away from active duty.

The most obvious type of Reserve job is flying…ideally an aircraft in which you are, or have been qualified. After a mountain of paperwork, you just change the patches on your flight suit and keep doing what you’ve been doing for years. Your unit will probably want you to give them a full week of work each month, as a minimum. Doing your Reserve work in one chunk has beneficial logistics. It’s easy to plan for in advance, it’s easy to work around your airline schedule, and it gives you time to adapt for weather or maintenance delays. This plan also makes a reserve job commutable. You could choose to live at your airline base and travel to your Reserve job. Most units don’t love this, but if they’re located at a true garden spot like Cannon or Laughlin they don’t have much choice.

If you do happen to join a unit where you want to live, life gets even better. You can work individual days that are planned around your airline flying. If you do it right, you can drop your kids off at school, go fly, and be home in time for dinner. If you want a little extra money, you can work more than the minimum without having to sacrifice much. This is far easier than going away for a solid week each month, and it’s a great option.

You don’t even have to fly the aircraft you were qualified in. Most units will send you to training if you’re the right fit. I’ve even heard rumors of heavy pilots joining fighter units. It’d be a lot of work, but this might be a way to fulfill the dream of a lifetime.

There are also RPA units popping up all over the country. They need help filling our military’s insatiable appetite for ISR support. Though it’s not the kind of flying we all love, it’s a dynamic, challenging, fulfilling mission. As a voluntary, part-time gig, it’d be a great way to continue serving and earn a retirement. Most of them are hurting so badly for help that they’ll give you as much full-time work as you want. Once you get hired by an airline, it’s just like working at any other Reserve flying squadron. These units are even showing up in some pretty great locations. You could do a lot worse!

Of course, flying isn’t your only option. Yes, those of us who leave active duty for the airlines probably list hating staff work as one of our main reasons for getting out. However, it might be something you could stomach for a few days a month in exchange for everything else this career path can give you. There are jobs in Air Operations Centers throughout the country (or world), regular staff jobs, jobs serving mugs of blue Kool-Aid at the Pentagon, and all kinds of other opportunities. All you have to do is start searching.

If you land one of these non-flying jobs as a regular part-time thing, you do it as a “Traditional Reservist.” You show up at the same office every month and serve basically the same function. However, there’s also a type of Reservist called an Individual Mobilization Augmentee, or IMA. In my mind, this is sort of a Reservist Minister Without Portfolio. The military has all kinds of needs that go unfilled. Sometimes these needs are very short-term. If they can’t find an active duty or regular reserve body to fill a role, they post a request for anyone else to help out. As an IMA, you basically shop job boards for these kinds of deals and take whatever you feel like. It’s up to you to get enough work to meet the minimums. We’ll see in a moment that you could accrue enough points to get credit for a year of service with less than four full weeks of paid work. As an IMA, you aren’t permanently assigned to any of the squadrons where you work. You get to pick and choose your jobs as you like.

If you’re really bad at math, or just uncontrollably patriotic, you can also pursue my type of Reserve job. I’m what’s called a Category E Reservist. This is enough of a separate topic that we’ll save it for Part 3 of this series. For now, let’s just say that as long as you don’t mind some trade-offs, it’s a pretty easy way to fulfill your minimum annual requirements.

Speaking of pieces of flair, how much does a Reservist have to work?

The Reserves work on a points system. Four hours of work equals one point. (4H = 1P) You can log up to 2 points in a day (meaning you should never work longer than 8 hours, or you are working for free.) When you join the reserves, they give you point credit for your active duty service…1 point per day. I’d served just over 11 years when I left, so I had just over 4000 points.

The points system gives you two options for reaching retirement. The first, more difficult way is to accrue 7300 points…the equivalent of 365 days x 20 years. At this point, the military equates your service to that of someone who did 20 full years on active duty…and grants you an active duty-style retirement. You immediately start collecting 50% of your base pay (or 40% if you were lucky enough to get in to the new BRS) and live happily ever after.

It’s tough to achieve this type of retirement as a part-time Reservist, but between logging 2 points per day and taking some deployments, it’s theoretically possible. If you had 15+ years of service when you separated from active duty, you could just take 5 years of full-time orders and easily reach your 7300 points.

For those of us who don’t feel like working that hard in the military anymore, there’s an easier way. Instead of going for points, you go for years. You just need to reach 20 “good years” of service, and you can retire. A good year is one in which you earn at least 50 points. Math, math…(4 Hours / 1 Point) X (50 Points)…means roughly 200 hours of work per year..(200 hours / 8 hours…carry the 1 = 25 days). Easy, right? It gets better though. The Reserves give everyone 15 “participation points” every year for free. That means you only have to earn 35 points…by doing 140 hours of work (17.5 days). Suddenly that IMA option is pretty attractive, isn’t it?

Unfortunately, this type of Reserve retirement isn’t as lucrative as an active duty one. Instead of giving you a fixed percentage of base pay, this system pays you a certain amount of money per point. That figure varies, but for an O-5 it’s roughly $0.60 per point in monthly pay. That equates to a monthly pay of $0.15 per hour that you work as a Reservist. Unfortunately, this pension doesn’t kick in immediately either. You start collecting at age 60, though if you’ve been deployed that date moves a little earlier (basically you get 6 months off your sentence for every 90 days of orders).

Though I hate to look a gift horse in the mouth, think about all this for a second. Let’s say you start collecting this retirement at 60 and die at 100. For every hour you worked as a Reservist you get $0.15/mo in retirement. That’s $1.80 per year, or $72 total over 40 years. It’s better than nothing, especially if the economy tanks. Plus, you’re getting paid a few hundred dollars per day for your reserve work. However, you need to realize that this carrot you’re chasing isn’t all that impressive.

Although I argue that the pension itself is far from compelling, it’s still a steady stream of passive income. Between that money, access to affordable healthcare, and the fulfillment you can get from service in the Reserves, I assert continuing your service there can be worthwhile. But you have to consider the opportunity costs associated with dropping 1 or 2 trips a month at your airline…but thats another article as well.

What’s that? You finally realize active duty doesn’t offer you anything you value that you can’t also get in the Reserves? Excellent! Now, how do you find the right job?

First and foremost, this is a point where networking comes in handy. Hopefully you’ve been a nice person throughout your career. You’ve taken the time to get to know people, you’ve been helpful, you’ve proven yourself to be a competent aviator and officer. You should start looking/asking around to see if any of your friends and acquaintances have any leads…maybe they’ve ended up in the Reserves themselves. It’s not unheard of for this method to reveal job opportunities that aren’t even public knowledge yet. If a friend knows you well enough to realize that you’d be perfect for the job and a great fit at the unit, your interview process could be rapid and painless. This is probably the best way to find a Reserve job.

If you did an assignment teaching pilot training, you definitely instructed some Reserve students. If you were the cynical jerk who hated being there and let your disdain for your students showed with every word and facial expression, don’t bother calling. However, if you were the type of IP who could be fun and encouraging while still ensuring that your students learned what they needed, then you can probably get a few job prospects just by giving Stanley a call.

In addition to this, I’d start looking online. Naturally, the Guard and Reserves have their own websites with job listings. (https://goang.com/careers, and https://afreserve.com/jobs/, respectively. The other branches probably have similar sites, but I’m fluent in Air Force.) Websites like BogiDope also keep updated lists running. (https://bogidope.com/military/) MilRecruiter even has a cool map that will overlay Reserve units and airline bases for commute mitigation planning. (https://app.milrecruiter.com/Squadrons)

I recommend you pick a few different jobs/units that make sense for you based on location, aircraft/mission type, and whether you know anyone there. If possible, it’s always better to reach out to someone you know at a unit to ask them about their hiring environment. That person should be able to refer you to their recruiting officer. However, most units are also accustomed to cold-calls, so don’t hesitate to proceed VFR-direct and ask for their application materials if you don’t know anyone there.

The application and interview process at a Reserve unit can be pretty involved. The best preparation for it starts years before you even think you’ll need it. In order to be attractive to a Reserve unit, you need to be a good pilot, a good officer, and a good person…and be “Scrolled” (more on that later).

As a pilot, you need to make sure you take the time to achieve as many qualifications and certifications in your aircraft as possible. If you were never airdrop qualified, you immediately make yourself a lot less attractive to many C-130 and C-17 units. If you were never receiver AR qualified, you’re plenty useful to a KC-135 unit but downright unattractive to a KC-10 or KC-46 unit. Anything else that’s unique about the aircraft you want to fly in the Reserves is something that you want to be qualified to do. NVGs, unique low-altitude flying certifications, weapons qualifications, functional check flight pilot, etc. You need to be a flight lead/aircraft commander, if not an IP. It might not be the end of the world if you’re only a wingman/copilot, but if that’s the case you’re just starting things out with a handicap.

There are also job-related schools that make you more valuable to a potential future unit. Advanced Instrument School, Safety School, Weapons School, a Mission Commander’s Course, etc. all make you extra useful, and extra attractive.

Getting chosen for these special opportunities isn’t guaranteed as an active duty pilot. Sometimes, it’s as much politics as it is need- or skill-based. However, you can at least prioritize your career to give yourself the right opportunities. You need to work hard and fly as much as possible. Sure, there might be some other kinds of rewards in working on a science projects for the Group Commander, being the Wing Commander’s executive officer, or taking command of a maintenance unit as a Major, but most of those opportunities will not translate into you being more attractive at a Reserve unit. (Unsurprisingly, these non-flying “opportunities” won’t make you more attractive to the airlines either. If you aspire to hold a flying job after active duty, your priority on active duty should be…wait for it…flying.)

While a Reserve flying unit won’t be looking for a master executive officer, they do need people who have demonstrated an ability to stay out of trouble and avoid creating extra work for everyone else. You should at least make sure you did the Professional Military Education appropriate for your rank. A great Reserve unit will make fun of you for having accomplished it, but the truth is you’ll be less trouble for your future commanders if you just got it done. You need to show a regular career progression through shop chief and/or flight commander positions and beyond, if applicable. They need people with experience in the different areas of running a squadron and leading people. You should also be able to show that you deployed and logged some combat time. For anything except an F-15, F-22, or F-35, combat hours should be pretty much a given right now, but more is always better. (Syria may be helping out some of those pilots now too.) Your unit needs someone with valuable, real-world experience.

While it’s important to maximize your attractiveness as a pilot and as an officer, probably the most important part of the selection process for a Reserve unit is making sure that you all like being around each other. If they hire you, they’re committing to spending significant amounts of time with you over the next 5-15 years. Either they choose good people, or they’re responsible for making themselves miserable.

This is another area where your “preparation” should have started years ago. Aviation is a small world and there is a pretty decent chance you know someone at this unit. What is your relationship with him or her like? If that person can vouch for you, things are much more likely to go your way. Even if you don’t know anyone at the unit, they probably know people who know you from elsewhere. I guarantee they’re going to ask around. You probably won’t get hired based solely on reputation, but if your unit has several applicants, a bad reputation could be enough to ensure you don’t get invited for a visit.

There are also opportunities to interact with units you might be interested in throughout your active duty career. Are you in charge of inviting people for good deals at your base airshow? Maybe you get to help organize exercises or air refueling opportunities with other units, or have the ability to decide where your jets go for DACT practice. (Working in a Plans Shop could be one of the best sources of Reserve unit networking out there.) Occasionally, units will send a pilot or two to help each other fill spots on a deployment. Keep your ears open in case a unit you’re potentially interested in needs help. Wouldn’t you love to be able to say something like this at an interview: “Yah, I got to deploy with you guys to Bagram a few years ago. I flew with Jonsey and Bam-bam. I guess you had a copilot drop out last-minute because his wife had a baby. It was a great deployment…I’m glad I found out about it in time to volunteer”?

I feel like the Social Network generation has sort of forgotten about real-life networking. It’s tough to meet new people if your nose is buried in an iPhone while you’re hanging out at Red Flag. Don’t be that pilot! No matter where you are, talk to people. Don’t be the obnoxious, over-eager kid pinging off every wall. It might take some practice, or even some mentorship, but you should take advantage of opportunities to talk with, and even learn from, other people whenever you can.

TPN is also a great way to start meeting people. A post like, “Would anyone from (Unit X) be willing to answer a couple questions for me?” might be enough to get started. I’ll also take this opportunity to give another shameless plug for our upcoming conference, TPNx. This event will be packed with fellow aviators from all around the country, and many of them will be pilots in the Reserves. One of your goals for the conference could be to meet people from at least 3 different Reserve units. It could be the way to find the exact lead you need. (Conversely, if you have a job and some pull at a desirable Reserve unit, you could end up enjoying a lot of free drinks!)

Once you make contact, the unit you’re interested in will send you an application package. Be sure to follow their directions exactly and keep things neat. If you’re unsure about something, ask their recruiting officer, but don’t be a pain in the neck. Try to figure things out on your own.

If your application is competitive, they’ll probably invite you out for a visit. Some squadrons like prospects to “rush” the unit before a formal interview. They want you to meet everyone and hang out at a Roll Call or other social function to try and see if you’ll fit in. If they offer this opportunity you should absolutely take it. If you’re not sure whether a pre-interview visit is appropriate, ask someone you know at the unit…even if it’s just the recruiting officer. If you show up on this type of visit, consider bringing a liquid gift for the squadron Heritage Room. Don’t make it so lavish that it looks like you’re trying to buy your way in (they’ll think you’re compensating for something,) but make sure it’s nice.

If you get invited for an interview, follow instructions. Bring and wear the right types of uniforms or civilian clothing. Be yourself, but take advantage of opportunities to talk to and get to know people while you’re there. They’re not looking for an aloof wallflower. When you’re arranging plane tickets home, leave yourself enough time that you don’t have to hurry away the moment the scheduled events are over. There’s a chance you’ll get invited to a no-notice social function, or just end up with a chance to hang out for a little longer. If you get an offer for something like this you need to be able to accept!

At your interview, you should be the embodiment of Humble, Credible, Approachable. (If you’re a funny person, make sure Humorous shows in there. If not, don’t try too hard because it’ll just make your lack of humor more obvious.) Yes, you’re applying to this unit for your own good. However, your message needs to be the value you can bring to them. Without bragging or seeming like a know-it-all, you need to be able to show them why they will have more fun, be more effective, and have an easier time as a Reserve unit if they hire you. It’s a tough balance to strike, so you should probably practice your interview skills with some trusted friends beforehand.

Getting yourself scrolled is also an important step that can delay things for months. Any inservice recruiter can add your name to the scroll process. Essentially it is a list that verifies that you are eligible to hold a commission as an officer in the reserves. It is a process that you can be proactive about, even if you don’t have a unit to go to yet. You can start it when you are still on active duty and forget about it. Time is the enemy here…there is not way to waive, expedite or ignore getting scrolled.

Most units also prefer to hire locals, or people who have always wanted to settle down and become locals, because they want you to have the most flexible work schedule possible. They also want people who are interested in social interaction outside of just work. For this reason, just like with choosing an airline (https://tpn-go.com/airline-comparison-part-1/), location is extremely important in choosing Reserve units.

You should be looking for units where you want to settle down anyway…it will improve your life significantly. If you can match a Reserve unit with your airline domicile, you’ll have hit a true jackpot! Your ideal interview situation will include you explaining why you love that area, what connection you have with it, and why you and your family are very excited about the possibility of moving back. If you’re not from that area, be honest about it. If you’re honestly willing to move there, it’d be good to be able to mention that you and your spouse flew out there a few weeks ago to take a look at the area. That trip may also be a good time to rush the unit, if appropriate.

If you’re not planning on ever moving there, be honest about that too. Don’t string them along. Most units have at least some commuters and they’ll give you consideration if you’re a good match otherwise. You wouldn’t want to start off a marriage by lying to your future spouse. Don’t start this relationship that way either.

The number and variety of Reserve service options are so plentiful that it could take you quite a while to figure out which one will work best for your family. If you lack education there, the best thing you can do is find a Reservist, buy him or her lunch, then shut up and listen. Do this a few times with a few people working in different types of Reserve job structures. Not only will this educate you, it’s a great way to continue your networking process.

Figure out what type of Reservist you want to be, find a few units that you’d like to join, send out your applications, and treat the interviews like big deals. Never take it for granted that they have to hire you. Guard and Reserve units are basically families, and if you come in cocky it will not go well. There’s a lot involved in each of those steps, but the basics aren’t cosmic. If you’re open-minded about the types of jobs you’re willing to do, I’m confident that you can find an opportunity that works for you.

There you have it, a primer on some types of Guard and Reserve opportunities with some basics on how to get hired for one. Rules for the Guard are slightly different, but more or less the same process. As I mentioned, this only scratches the surface of what’s available out there. Before I leave the rest to be addressed in a future podcast, I want to talk more about being a Cat E reservist. Stay tuned for that in Part 3.

BogiDope is a proud sponsor of The Pilot Network, and this post is republished from their site with permission. You can read the original post here. You can also get more great TPN content on the TPN Community Website, on their free TPN-Go app (iPhone or Android), in their quarterly TPNQ magazine, and on their Podcast.