Naval Aviation – Cultures, Attitudes and Career Path

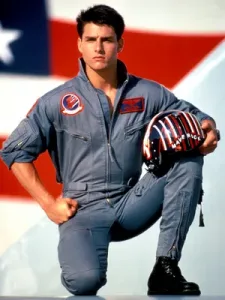

If you’re interested in figuring out if Naval Aviation seems like your cup of tea, you’ll be interested in what sort of folks do the job, as well as what kinds of attitudes and cultures prevail. This is a topic probably worthy of its own novel and has had more than a few written on it—shout out to CDR Ward Carroll and his excellent Punk’s War series of novels, which are a great view of the culture from someone that’s been there—as well as a few feature films. You may have heard of at least one or two… But let’s try to cut through the Hollywood and get to the real deal, shall we?

Table of Contents

The Key Ingredients

Here’s my take on the things that define the attitudes and drive the culture of Naval Aviation:

1. FLEXIBILITY. I’ll allude to this throughout these articles, and I’ll double down on it now: “Semper Gumby” is a lifestyle. There are times when this is awesome. If the day’s mission just doesn’t make sense based on the current circumstance, the pilot on the scene is not just empowered to flex, it’s expected that they do so. This enables the enterprise to quickly react and solve problems, and if you’re one of the folks out there that gets a rush when you get ‘thrown a curveball’ and successfully accomplish the mission anyway, this is your business for sure. Memorizing reams of manuals is nice, but to make flexibility work, you need to have a bunch of different skills and the ability to choose the right approach (which may not have been the planned or briefed one!) under pressure. There are times when it is less awesome, like when the higher-ups decide to go ahead and send your unit to sea a month early over Christmas because Nation X just did Y and your unit is on the hook to react. This sort of flexibility requires a certain sense of fatalism to deal with effectively. . . but it does tend to generate a sort of “We’re all in this together” feeling, even if it sometimes smells like gallows humor.

2. DECENTRALIZED LEADERSHIP. To make 1) above work, you have to empower your junior leaders. While any organization with as much communications technology as the military has will inevitably suffer from occasional bouts of intrusive leadership, the Navy’s history lends itself more than the Army or Air Force to empowering the independence of its decision makers. Ship captains of yore did not have time to wait three months for a mail run before deciding where and how to employ their vessels; they just received some vague instructions from the boss when they left port and were left to their own devices to figure out how to execute the commander’s intent. To learn how to work like that, the Navy tends to take a similar attitude toward its junior officers, telling them less of “how to do it” and more of “what needs to be done.” The idea is to give folks plenty of rope and it’s over to them whether they lasso the enemy with it, or their own neck. There is a lot of decision-making at the junior and middle-grade officer level. If you step up and start making good things happen, you are likely to be allowed to continue to do so. At least until you screw it up, anyway. This is cool for some people, and very scary for others—consider yourself warned.

3. TACTICAL EXCELLENCE ENABLES LEADERSHIP—AND OLD PILOTS FIGHT. One thing you won’t see very often in any military service is senior officers doing the same tactical functions as the junior pipe-hitters. As a new pilot, you’ll be expected to shut up and learn, learn, learn, ‘drinking from the firehose’ as we say. But as you get more senior, you will retain the requirement to be tactically excellent while piling on more and more responsibilities. This can be stressful, but it’s awesomely rewarding, because even senior guys are expected to get out there and do what they signed up for. Very few military career paths see senior officers with 15, 20, or more years of service out there with the proverbial sword in their hand, standing on the front line on Day 1 of the fight. Not only is this expected in Naval Aviation, it’s a requirement: the culture is such that we expect our senior officers not just to fight alongside the junior ones, but to excel. Thus, to lead a bunch of Naval Aviators, the requirement is that you be among the very best in the crowd. It isn’t a “can’t-miss” system, but it does tend to yield bosses you respect.

4. MICROCULTURE. As you can imagine, a culture of flexibility and decentralized leadership leads to a situation where there’s a lot of variability from unit to unit and platform to platform. When folks have the opportunity to innovate and change things at their level, standardization across units becomes a bit tougher. The Navy’s personnel system moves people around a lot, adding to the churn. You might check into a squadron and find it a total mess and then come to find it firing on all cylinders and winning awards 18 months later with a new CO and some turnover among the junior officers and senior enlisted leadership. Realize, as well, that there are huge gaps in culture and attitude from one platform to another, and some communities are better fits for different types of personalities.

Expectations

Notice what I didn’t mention? Ego, overconfidence, excessive risk-taking? Sorry, fans of the 1980s, but these things are not the drivers of the culture. Are there confident people in Naval Aviation? By the bucketload, of course. Professionalism is the name of the game, and the best professionals tend not to be risk-taking egomaniacs. The hardware is too technical, the mission is too difficult, and the stakes are too high for those sorts of things to rule the day.

Notice what I didn’t mention? Ego, overconfidence, excessive risk-taking? Sorry, fans of the 1980s, but these things are not the drivers of the culture. Are there confident people in Naval Aviation? By the bucketload, of course. Professionalism is the name of the game, and the best professionals tend not to be risk-taking egomaniacs. The hardware is too technical, the mission is too difficult, and the stakes are too high for those sorts of things to rule the day.

It’s not all roses, of course. Naval Aviation culture ferments some attitudes some folks don’t enjoy. The Navy revolves around deployments, and not every person or family can handle the constantly-changing workup cycle and deployment schedule. It’s also a system that assumes a certain thickness of skin, the idea being that a thick skin promotes an attitude of working through problems that is useful in combat. Banter is the name of the game, and generating humility among very confident people is what its function is. Note how similar the words “humility” and “humiliation” are and you’ll get the idea of how Naval Aviators seek to encourage humility among its members. Naval Aviation nicknames – “Callsigns” in aviation parlance – are typically references to something you screwed up, as opposed to Air Force nicknames which all seem to be super cool. Any Naval Aviator worth his wings is going to poke fun at the Air Force pilot they see at the Officer’s Club with “Buzzsaw” on his nametag. If you see a Navy pilot with a similar nickname, check to see that he still has all his or her fingers. Ready room banter (and the occasional sophomoric joke) are big draws for many, but less so for others.

Career Path Outline

If all of that sounds good—great! Here’s a super-quick summary of the path you’ll be getting yourself into. Worry not, I’ll expound upon it all in later articles.

Step 1: Get a commission. The United States Naval Academy (USNA), Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC), and Officer Candidate School (OCS) are the main sources. Enlisted-to-officer programs exist too. You’ll be expected to have a college degree.

Step 2: Initial Training. You’ll go through a lengthy (two to four year) training pipeline from the time you pin the ‘butter bars’ on your shoulder until you have a set of golden wings on your chest. That’s a long grind, and sometimes it will feel like every day is the final exam, because it very well might be—prepare yourself. When you wing, you will incur a service commitment of six to eight years. It doesn’t take a math whiz to figure out that walking down this path is going to be a serious, decade-long (at least) commitment.

Step 3: Junior Officer Fleet Tour. The cornerstone of the freshly winged aviator’s career will be in their first deployable tour in their platform. The learning is not going to stop, but by then end of this (typically three-year) tour, you’ll have a lot of qualifications, a lot of experience, and probably some cool stories to tell to your grandkids.

Step 4: Junior Officer Production Tour. After your fleet tour, you’ll likely head to a shore tour, and it’s very likely this will be as an instructor somewhere, teaching future aviators at anywhere from the basic to the graduate level.

After these steps, you’ve likely discharged your initial commitment, and you’ll be up for promotion and more responsibility. This is the time where you make the call about staying in or getting out. One thing I’ll point out here: the Navy does have reserve flying units, but they are nowhere near as numerous as their Air Force/ Air National Guard brethren, and they are all staffed by aviators that have completed Steps 1 through 4 above—there’s no direct accession to the very airline-friendly reserve components as there is in the Air Force.

Conclusion

Hopefully you’ve now got a sense of what Naval Aviation is all about. Next up, we’ll talk details about the “what” and “where” of it before we start going into detail about what those steps above really look like in detail.