Military Leave on Probation

Feliz Cinco de Mayo, BogiDope readers! The following is reposted from the members-only TPN Community website with minor revisions. It addresses USERRA. If you have more questions about that law, be sure to read our original article on the subject.

“Would it be a problem for me to take long-term military leave during my probationary year at a major airline?”

I hear this question all the time. It’s common because a military pilot leaving active duty needs to consider both airline and guard/reserve (hereafter collectively ‘reserve’) jobs at the same time. Neither hiring process offers a fixed schedule for long-term life planning, and most of them show up as one-time offers.

This post is my attempt to tackle this question. My simplest reply is: “If you have to ask, don’t you already have your answer?” However, that’s far from the end of the issue.

(Side note: Aaron Hagan from Emerald Coast wrote a great post about Avoiding Square Corners. I present this as one specific square corner to avoid.)

An author named Simon Sinek wrote a pretty decent book called Start With Why. I like his premise, so before we go any further I want you to sit back and think about the ‘whys’ driving this transition in your life.

- Why are you leaving active duty military aviation?

- Why are you pursuing an airline career? (Why not a job as a real estate agent, project manager for a defense contractor, or a day trader instead?)

- Why are you planning to continue your service in the reserves?

The answer to #1 is pretty well-understood by those of us who don't participate in the Pentagon's daily blue Kool-Aid guzzling contests. (If anyone from the five-sided echo chamber wants to know the details of that answer, just let me know...I'll be happy to explain it all to you and explain exactly how to fix all your problems.)

Money is an important factor in #2, but it's about far more than that. It's about having a lot more time with your family, giving your family some stability, and having more choice in life. It's about being valued for doing what you love to do, being compensated realistically for your efforts, and not being coerced into giving extra time without requisite compensation. It's also about being in control of how much stress is in your life...and being the person who gets to adjust that dial as your needs and capacity change over time.

I feel like #3 tends to vary more from person to person. Some are focused almost completely on retirement. They need the security of the government gravy train. For some, getting free health care for life is more important than joining the check-of-the-month club.

(I feel like I've thoroughly demonstrated how military retirement can't compete with airline compensation. See: this, this, this, this, and this. The taxpayer-funded military retirement represents less money for your family; however, I generally regard military retirement as carrying less risk than the airline industry. Your family's risk tolerance is an important part of your career transition calculus.)

Others want to serve because they're just patriotic Americans. Active duty has made everything so painful that even love of country isn't enough to keep some people in, but they can give the service they want to give without the insanity of active duty by joining the reserves.

Some people just aren't ready to stop being awesome. Military aviation offers unique opportunities to fly fighters, do NVG landings, rescue people in helos, bounce around the world in one of the largest aircraft ever built (because size really does matter, right?), etc.

I'm considering some reserve flying opportunities. I don't need the money (though I won't refuse it, or the cheap health care.) I have no illusions about it being particularly awesome, per se. However, I do love the flying. I also love instructing and feel like I could continue to make a difference in some young pilots' lives and serve my country as a reserve pilot. As compelling as my personal reasons may be, I chose to establish my airline career and stabilize things for my family before giving serious thought to finding a reserve flying unit.

Now, having considered the ‘whys’ that prompted you to ask your original question, I want you to think seriously about which ones are the most important. The best part about our situation is that you aren't limited to picking just one. You really can have it both ways. You can be and airline pilot and fly in the Reserves. However, you may need to prioritize one over the other in the short-term future...give up time in service or a few seniority numbers to make sure the most important part of your future career is taken care of first. This ranking can and should help drive your personal response to the question at hand.

Now that we have figured out our ‘why’ let's use it to start framing our problem:

Unfortunately, both the airlines and the Reserves are governed by economics. If an organization is going to hire you to be a pilot, it needs you to start working for them as a pilot right away. Training you costs a lot of money and it does them no good if you ditch them for your "other" job the minute you get qualified. They aren't trying to make life difficult for you here…this is simple economics at work.

Your potential future employers address this in different ways.

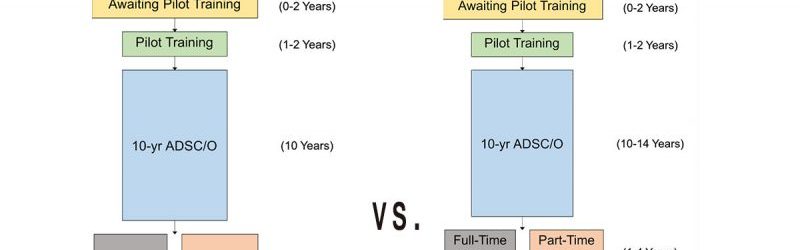

The military has you sign a contract that essentially gives up some of your freedom in exchange for their good deal. They can give you orders requiring you to serve on active duty for the duration of your training and possibly longer for "seasoning" or even deployment. You can't usually just turn that down. If you insisted on trying, they could potentially just cut you from the team and move on.

The airlines have something called probation. Since the airline industry is heavily unionized, it's extremely difficult to fire a pilot. To mitigate that, the airlines have insisted the unions give them one year at the start of each airline pilot's career to identify and eliminate bad eggs. During this probationary year, your union-endorsed contract probably gives your company the power to fire you at any time for any reason. Talk about high threat!

(Don't worry, I believe that you pretty much have to try to get fired while you're on probation. The only stories I've heard about probies getting the boot involved pilots who just couldn’t figure out the flying despite receiving tons of extra help, had severe attitude issues, or engaged in grossly dishonest/immoral behavior.)

The other thing to consider is that we intend to spend a long time on these career paths. The reserves have to hire with the expectation that a pilot could be with them for 10-15 years, at least. Most airline careers will be longer than a pilot's previous military career, even if he or she retired. If the pilot separated from the military at the 11-12 year point, this airline career could be 2-3 times as long as he or she spent in the military. This is longer than some marriages last. The organization needs to make sure that it hires the right people. The pilot also needs to start that relationship off properly. The last thing any of us wants to do is make our new ultra-long-term employer angry by ditching it for a few months, right after training, to pursue our "other" job.

The US government has an ace in the hole here. The Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act of 1994 (USERRA) mandates that employers let reservists take military leave from their primary jobs for military duty. Most airlines seem more than happy to support their reservists; they publicly voice their pride in employing us. (Not that they have much of a choice...USERRA is Federal law, after all.)